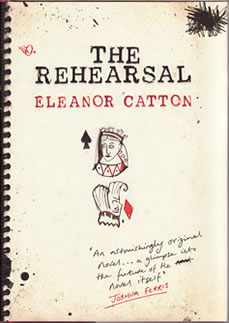

Eleanor Catton's début novel The Rehearsal is that rare creature—a book that does something really different. With unusual unity of style and content. Catton skilfully orchestrates competing, overlapping and contrasting narratives to explore the nature of the performance of identity. Written during the masters' course in creative writing that she took at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, The Rehearsal was published by Victoria University Press in 2008, when Catton was just 22. Among others, it has won the Montana New Zealand First Book Award, the UK's Society of Authors Betty Trask Prize, and at time of writing, has just been longlisted for the UK Guardian's First Book Award.

The book weaves together two complementary stories around a single theme. At the heart of the plot is the discovery of a teacher-student relationship at the local girls' high school, between the band conductor Mr Saladin and Victoria, one of his pupils. Victoria's sister Isolde and her friends must come to terms with the sudden transition to an adult, sexual world in the wake of the exposure of the affair. Much of this transition takes place under the watchful eye of the saxophone teacher, a sinister and manipulative figure who teaches many of the high-school girls—including Julia, a defiantly unconventional girl in Victoria's class, who is drawn to Isolde.

A second narrative thread is set amongst the staff and students of a nearby drama school. The school's first-year students (who include among their number the sensitive and unconfident Stanley) decide to use the scandal as the basis for their end-of-year production. As the production progresses towards its opening night, Stanley and Isolde are also drawn together after a chance meeting near the saxophone teacher's studio.

The drama-school strand includes scenes set explicitly on the stage, but the metaphor of the stage also suffuses the high-school world, blurring the lines between reality and imagination. Characters speak lines that convey what they are really thinking rather than what is socially conventional; music and lighting cues punctuate the text; several of the characters harbour a desire to "play" each other, and to escape the roles that they have been allotted. The deliberate destabilising of reality compels the reader to a deeper understanding of the development and nature of identity. Joshua Ferris called it "a glimpse into the future of the novel itself." It's spine-tinglingly good.

I caught up with Eleanor at the Edinburgh International Book Festival to discuss The Rehearsal, her writing and what it means to her to be a New Zealand writer.

You've referred to interviewers seeming to be obsessed with knowing "what really happened" in The Rehearsal. Did you feel when you were writing the book that you knew what really happened, or were you in a way withholding the "truth" from yourself?

EC: The manuscript of The Rehearsal started off as my masters' thesis, for my MA programme in New Zealand, so it was workshopped twice during that year - once when I'd written maybe about 20,000 words, and once when I'd written about 40,000. In both of those workshops - especially the first one - the question that kept on coming up around the group was, what are the rules of this universe? That was the phrase. Who's watching this performance? Is it even a performance? Who's the director? What's the purpose of the production?

I remember being really surprised. It wasn't that I knew what was going on, or that I didn't know what was going on, it's just that I'd lost the sense of the strangeness of the book, of picking it up, and thinking: oh! So it was interesting to me that they were so hung up on this question. I think that probably pushed me to resolve the question of what's going on maybe more than I would have done if I hadn't heard that confusion so early on in the process.

I felt a real attraction to theories of performance, the theoretical ideas behind the book. I do believe that we do perform our identities; I believe that gender theory's got a whole lot going for it, it's a really compelling theory. So when people were saying, well, are they on stage or aren't they, my answer would be, yes - but not in a way that's peculiar to the book.

There's a tension in the book between wanting to escape yourself - but also beginning to realise the power you actually have to project your own identity, or to define it for other people. You catch your characters at a time when they're becoming aware that this is possible.

EC: One thing's that's weird about growing up in the world right now - being of my generation - is that you really can choose who you want to be. People my age have such a keen awareness of "this is what an emo is" or "this is what a punk rocker is". If you make all the choices - if you go down the list and you tick 'yes' to all these questions - then you become that person. We have so many choices about how we choose to dress ourselves or how we choose to do our hair - reinventing yourself is so possible. If you think back a hundred years, it was impossible. It's such a modern phenomenon.

The other weird thing is that we're confronted so often with images - all the time. We can see what things look like - what love looks like, or what success looks like - so long before we have a chance to make up our minds about what it might mean to us. It's a strange time to be alive. I'm really interested in group dynamics. In The Rehearsal, I explored it more in the drama school sections: at the beginning of the year, when all the drama school students define themselves and get a place for themselves, poor old Stanley's about two steps behind. By the time he rocks on up, there's nothing left.

The Rehearsal is so patterned and structured. Do you find that you're shaping the structure before you start, or are you an instinctive writer, and the plan is almost imposed afterwards?

EC: I definitely didn't plot ahead. What seems to me now to be the most important scene in the book is the scene where Isolde and Julia act out the saxophone teacher's memory; the girls come together, and you see for the first time, or most clearly in the book, how much the girls are an overlay of her, and of the performance of her life. That scene was pretty much the last scene I wrote - which is so weird to me now, because it seems so crucial; it seems like of course, the book was going - there!

The way I conceive of it is that I set everything moving, and then I sit back and have a look at it - and that's where the book wanted to go. I came to respect the fact that the book had its own consciousness, its own momentum and its own agenda, and I had to listen to that. It sounds sentimental, but I couldn't have known at the beginning what the book would teach me. When I was writing it, I had this master document that I would always keep open on a separate screen beside me. I had a list of all of the scenes and just a very brief, maybe 2- or 3-word summary of what happens in those scenes. I did a lot of shuffling, especially in the drama school sections, because that's obviously non-chronological, whereas the other stuff is pretty chronological.

I saw a review that said, "the scenes of the novel were arranged like a pack of cards that had been shuffled." When I first started writing, I wanted 13 chapters. It would go up to 10, but then be labelled 'Jack', 'Queen', 'King' - but I didn't want to have the first chapter be 'Ace'. And then I ended up having 14 chapters in the book, and I didn't want there to be a Joker, so I ended up not using that format - but that was the idea I was working towards.

I've done a little bit of film editing - nothing very amazing, but just amateur film work with my friends. Shuffling around these scenes - seeing what changed when you juxtaposed different scenes - was really fun, the most fun that I had when I was writing, I think: so much like film editing.

How hard do you push the editing at the sentence level? There are so many sentences in the book that just seem to pivot perfectly - if you took one word away, it wouldn't have quite the same impact.

EC: I don't draft, really. If I think a scene is finished, then it will be finished. And I work really, really slowly. A sentence might take me about 4 or 5 hours - which makes for quite a dull day-to-day. Rhythm is really important to me. When the book was being edited for the New Zealand edition - it's the same edition as Granta's, they didn't edit it again - the editor that I worked with would often try and change something because it didn't quite make sense, and she'd put it in using tracked changes. And I'd track-change back to her and say, look, I know this doesn't quite make sense, but I don't care - because I need the alliteration there - or I need this for some reason.

In one of the very first scenes, the saxophone teacher is rhetorically asking whether her students' lives are very meaningful: she's saying, "your two-minute noodles after school, your candles on the dresser and facewash on the sink". The editor had put in a little question-mark, "facewash on the basin? because surely 'sink' means kitchen". And I said, "I know that sink is wrong, but 'sink' ends the sentence on a one-syllable word, on a hard glottal consonant - I can't have 'basin'!" It was tiny things like that, but they were often rhythmic, where I would put my foot down and say, no.

There's another one later in the book, describing the Head of Movement [at the drama school], where the sentence runs, "His instinct inclined towards simplicity and scruple, and yet he was not a scrupulous man." The editor's view was that it didn't make sense, because 'scrupulous' is not the adjective that is derived from the noun 'scruple'. I said, I know, but I don't care because I need the connection there, and I just really like the alliteration.

It's going to be interesting because it's being translated, and I'm not fluent in another language - it's quite weird to think that's all out of your control. It's being translated into 10 languages altogether - the latest is Finnish.

You use names in the book in quite specific ways: the Head of Movement is eventually addressed by name, but particularly in the drama school sections, most of the students are addressed as just "the girl" or "the boy", with the adults referred to by their jobs.

EC: There's only one character in the whole book that has both a first name and a last name - that's the conductor that they bring in to replace Mr Saladin, and she's Mrs Jean Critchley. That was really important to me, because there's a sense of security that you get when you know somebody's name: you can hang your hat on Mrs Jean Critchley - you know she's a person. I wanted the Head of Acting or the Head of Movement to remain a little bit more shadowy, and the saxophone teacher most of all. What we were confronted with at a linguistic level was always her role rather than her person. The word "teacher" just keeps coming up - and I like the mantra-like quality to that.

I did a written interview a while ago, which asked about performance, and I realised that all of the characters have something in common: the frustrated desire to escape themselves. It's true of the adults and the girls, I think. With the adults, it manifests as more of a frustrated nostalgia: they start idealising a past version of themselves as an attempt to escape what they've turned into - or they start idealising - puppeteering - the young adults in the same universe. For the girls, the desire to escape what they are is not nostalgia - it's a kind of yearning. I didn't realise that until I did this interview - that this was so much at the heart of the book. I think when I was a teenager I felt very much like I wanted to escape myself.

The character of the high-school student Bridget struck me particularly — when the drama school students discuss the significance of the card of the "Suicide King" in their production, I was convinced her death would turn out to be a suicide. Did you ever consider that?

EC: As soon as I realised that I wanted to use Stanley's father's suggestion that you could profit from the death of a classmate, I also realised that one of the girls had to die. I think that if she'd been a suicide, or if there'd been a suicide in the book, it would have opened up a whole lot of different questions that I didn't want to explore.

I actually worked in a video store when I was at the end of high school. Like Bridget, I started working at this store when I was 17, so I was not able to watch a lot of the movies that we rented. There was also an adult section, so technically I wasn't allowed to walk in - but you had to, because you had to go in and clean the shelves or whatever. It seemed important to put into the book, because it was so emblematic of these girls' lives: you can't stop them from seeing what they see.

Who do you feel has influenced you, and who do you admire (because they're not necessarily the same thing)? Reading The Rehearsal, I found myself thinking of Margaret Atwood's Cat's Eye, and Emily Perkins' Not Her Real Name.

EC: Emily Perkins went to the New Zealand Drama School, and I have a lot of friends that went there. I watched a documentary a couple of times about the Drama School, and took a whole lot of notes. Amazingly, the Theatre of Cruelty scene in the book is true - that happens at the New Zealand Drama School every year. When I first heard about it, my friend had been involved: she was a woman, but she'd had her shirt cut off her. It's cool that you mention Margaret Atwood: when I was a teenager, she was the one author - I've read so much of her work. She's just got such beautiful sentences.

In terms of influences just for this specific book, the answer I've mainly been giving is the graphic novelist Alan Moore. He's a really formally playful writer: Watchmen obviously, and then From Hell, a novel about Jack the Ripper, and also The Lost Girls. He plays with the way that he's using the images and the way they relate to the words in a way that I just found really exciting. There's a scene with the counsellor where you see it from both Julia and Isolde's perspective. I wrote that just after I'd read one of Alan Moore's books where he does that, so he seriously influenced me.

Muriel Spark's a connection that's been made by reviewers - The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, obviously, because Miss Jean Brodie's just so like the saxophone teacher. And it's a really flattering comparison - I like her work a lot. I like Iris Murdoch a great deal. I tend to read quite eclectically. This year, I've been reading pretty much all American authors - because I'm in Iowa and everyone else has heard of all these amazing authors that I've never heard of.

You've mentioned that you didn't progress for a long time beyond the first section of The Rehearsal as you just couldn't imagine the story getting any bigger. Yet you've also said you feel naturally more at home in the novel, and the short story form feels a little strange. How are you feeling about short stories versus novels at the moment?

EC: I don't read a lot of short stories at all, actually. Being at Iowa, there's a whole school of short-story writing that you have to have read to understand the Workshop in a lot of ways: John Cheever, Raymond Carver, Flannery O'Connor, Alice Munro, Hemingway obviously. There's a lot of people who now I've quickly gone and done my research, I can understand the way they teach short stories there.

But I love novels - I really like the relationship you form with a novel. I love re-reading - I re-read probably almost as often as I read. I just recently read Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. It was one of those books where you kind of put it aside, because you think, I'm just going to love this. I was reading it so impatiently because I knew I couldn't wait to re-read it - I found myself having to put my hand over the adjacent page to stop myself going too fast.

The thing I like about a novel is that you can't get away with cleverness in the same way that you can in a story. Sometimes a story can be just like some kind of rhetorical trick or an experiment - whereas with a novel, if you're going to set yourself up, you have to deliver - it can't just be a flourish. I don't really like experimental writing. I feel a lot of experimental writing exists to say, look at me, congratulations to me. To me, the structural playfulness of The Rehearsal is not necessarily what I want to be in the forefront.

In New Zealand, a lot of people criticised the book for being too 'thinky', too intellectual, not heartfelt enough. It bothers me because I feel the book is so sincere - it's trying to articulate an emotional question. The experimentalism of the form is necessary: the content presented its own form.

Do you feel a tension between loyalty to New Zealand - wanting to be identified as a New Zealand writer - and the parochial nature of the country?

EC: I think I've got a pretty healthy measure of scepticism about New Zealand culture. In a lot of ways, it's quite an anti-intellectual place, which I think is not that awesome. I don't think as a culture, we encourage people to be critical of - well, anything really. It can be a closed place in a lot of ways. But it's my country! It's the place where I grew up. It makes sense to me that The Rehearsal came out of New Zealand - it came out of that creative writing programme as well. When I got to Iowa, I realised that being on the margins a little bit as a country - as New Zealand is, geographically; we're not a heavyweight, really, in any sense — can be really liberating. Nobody told me that a novel had to be a certain way; at Iowa it is a little bit more like that. There are accepted truths - which you can still accept or reject - but the institution feels much more present there. In New Zealand, you feel much more alone as an artist. New Zealand's got some amazing writers.

There was an essay about New Zealand writing published by a New Zealand academic about 10 years ago, where he criticised New Zealand writers for writing what he called "global literature" - this kind of "placeless", I think that was the word he used - placeless literature that wasn't really about New Zealand or New Zealand-ness: it didn't really engage with what it meant to be a New Zealander. And in one way, my book is a total exponent of that idea - and in another way, it's not at all.

Do you think that living abroad changes your perspective?

EC: I spent one year in Leeds [in the UK] when my dad was on sabbatical, when I was 12 - but I was born in Canada, and we moved to New Zealand when I was six, so I've lived in a few different places. It does change your perspective - it's that thing of re-invention again, you turn up in a new place and you have to reinvent yourself. I feel really lucky that I've been able to travel a lot.

The short story that was in Granta recently - Two Tides - is a really New Zealand story - and was the first story I wrote at Iowa - it was kind of a homesickness? You start thinking about your country a lot when you're away.

The thing that I was struck most by when I first arrived at Iowa was how much I heard the word 'America' or 'Americans'. People of all ages were always talking about the country, what 'America' meant, what it meant to 'be American'. New Zealand isn't an idea in the same way that America is an idea - but we're not continually measuring ourselves against the nation in the same way. I've loved my time in America!

How do you feel about the migration in New Zealand publishing, with major publishers and chain bookstores moving to Australia and local bookstores closing down? Do you think there's any hope for things to wake up again?

EC: we should all be hopeful! The thing that I think is terrible in New Zealand is that a paperback novel costs 30 dollars, and a new DVD costs about 25. It's so difficult to be a reader - it's so expensive! People are doing great things in New Zealand though. My publisher in New Zealand is wonderful - it's a university press, but they've got a really strong commitment to publishing début fiction, and that's just so hopeful to me. Every year, Fergus the publisher will publish three or four first-time novels, and books of poetry. I haven't really seen the ugly side of it at all - it's such a family publisher.

Are there any particular New Zealand writers that you would recommend, or that you feel are under-represented and ought to be more widely read?

EC: definitely Janet Frame. I tried to set a Janet Frame novel in my class in Iowa for my students to read, and the bookstore didn't have it! So I had to change it. Elizabeth Knox: her book The Vintner's Luck has been made into a film that's just about to be released. She's a really zany, experimental, fringe fantasy writer. Maurice Gee, particularly his books for children - but he's pretty well-read, I think.

What are you reading at the moment?

EC: I'm halfway through The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño. I'm enjoying it hugely, but I've had to take a holiday, so in my holiday I'm reading Revolutionary Road for the first time. I read The Lover recently by Marguerite Duras - I really recommend it, it's like a punch to the head. I've been reading a lot of novellas because I've been travelling. The Vagrants by Yiyun Li - I strongly recommend that — an amazing novel that's only just come out.

What are you working on at the moment? You've mentioned a literary novel and a quartet of fantasy novels - are you getting much of a chance to work on those?

EC: I need to write the literary novel for my contract, and the fantasy novels

are just playing - but I'm working on the fantasy novels and not working on the

other project, which needs to change! As I was saying in the session the other

day, having this "hangover" after finishing writing The Rehearsal, I needed to

go into something completely different. The fantasy helped me change gears.

I have got an idea for this literary novel but I don't really want to talk about

it too much. It's going to be a little bit sci-fi, and set in the 19th century.

It'll be fantastical in the same way The Rehearsal is fantastic, and playful in

the same kind of way - I won't be able to escape that! But everything else will

be different.

http://www.granta.com/rehearsal