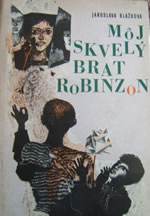

The eminent Slovak writer Jaroslava Blažková has a world view that is always ironic, even cynical,

her tone self-deprecating. Now seventy-five, she has been writing professionally since seventeen,

and has among her many credits a Hans Christian Andersen Award in 1964, a Mladé Letá Best Fiction

Prize of 1968, and the prominent SME Readers' Prize for 2005. She has written for children, young

adults and adults, short stories, novels and a memoir. Two of her works have been filmed, and

numerous fictions translated into thirteen languages. In her first book-length work, Nylonový

Mesiac (Nylon Moon), the protagonist boasts that "whenever he got into trouble, he tried not to

think about it. He had considerable training in this trait, and was understandably proud of it."

Her most recent book, a memoir of her caregiving in the last four years of her husband's life, end

with "These were years of confusion and hurry, filled with love and fury, despair and extravagance,

hellish, heavenly, but always full of life, life, life..." Her writing can be seen as encompassing

these three qualities: a dismissal of trouble, a longing to overcome, but most importantly a need

to live life to the fullest.

The eminent Slovak writer Jaroslava Blažková has a world view that is always ironic, even cynical,

her tone self-deprecating. Now seventy-five, she has been writing professionally since seventeen,

and has among her many credits a Hans Christian Andersen Award in 1964, a Mladé Letá Best Fiction

Prize of 1968, and the prominent SME Readers' Prize for 2005. She has written for children, young

adults and adults, short stories, novels and a memoir. Two of her works have been filmed, and

numerous fictions translated into thirteen languages. In her first book-length work, Nylonový

Mesiac (Nylon Moon), the protagonist boasts that "whenever he got into trouble, he tried not to

think about it. He had considerable training in this trait, and was understandably proud of it."

Her most recent book, a memoir of her caregiving in the last four years of her husband's life, end

with "These were years of confusion and hurry, filled with love and fury, despair and extravagance,

hellish, heavenly, but always full of life, life, life..." Her writing can be seen as encompassing

these three qualities: a dismissal of trouble, a longing to overcome, but most importantly a need

to live life to the fullest.Jaroslava Blažková had to leave her homeland and her highly successful career behind in 1968, after the Soviet occupation. Erased from public consciousness by the authorities, her works shredded, she was an unknown for over twenty years even in Czechoslovakia. Living in Canada, a master of Slovak language, but with only rudimentary English, with no prospect of ever being published again, led to a period of non-writing depression. The fall of communism in 1989 rejuvenated her. Some earlier books have been republished and she has written new ones. She has visited Bratislava repeatedly to triumphant response; lines at her signings are enormous. Slovak literary critics are increasingly studying her work; published interviews abound. A prominent critic, Ondrej Sliacky, calls her a "legend of modern Slovak prose."

In a 1997 interview she says, "Some griefs are inconsolable, some stages of life cannot be returned to. The year 1989 came too late for me. When I received a letter from Bratislava, asking how I imagined my rehabilitation, it seemed absurd to me. All I wish for is to have all my books in print again, accessible to readers." Readers in Slovakia have had a chance to discover or rediscover her work for the last twenty years. Readers in English are about to get those opportunities as well: currently, two translators are making her work accessible in English, one translating her short stories, another her recent memoir.

They walked along the flat land of the outdoor gardening centre, the woman and the boy. At the back the sun was reflecting off the greenhouses as if they were huge diamonds thrown into the rich loam. The air was redolent with clary sage, wilting cauliflower leaves, a field of outreaching, shouting carnations.

In a weary voice the woman scolded, "Don't dawdle, come!"

The child whined, "I am thirsty!"

But the boy crouched down. "Oh, look!" he cried out. From under the wet straw two dung beetles crawled out, metallic black, with rainbow flashes on their shells, a male with a female.

The child skipped along, ran after a blue icarus butterfly which, full of shivery blue desire, was chasing his mate.

The child began giggling. "Kulka! That is the funniest, mom! Dad is Kulka, I am Kulka, and the little one will be Kulka! The whole world will be made into Kulkas. You are sure it could not be Dusan Vodnar?"

The woman wiped her face. "What silliness is this?"

The woman sighed. The sky was grey-blue, a woodlark shimmered in the heat. Cucumbers crawled along the parched rows, their yellow funnel flowers sucked in the sun. Water dripped from a tap and the earth drank it in through the cracks.

The woman turned on the water, gave some to the boy. He snorted into her locked palms like a colt, a small pink animal with a moving snout. She tied a knot on each corner of a hankie, placed it on his head, and said,

He looked at her full of surprise and admiration, curious, as if suddenly she appeared to him in a totally different light.

She took his little paw, grimy with sand, and put it on her apron.

The child ripped his hand out of hers, as if burnt, and full of wonder his mouth formed an "oh". A moment of silence.

The boy stared at the pockets of her apron in fascination: "You carried me like that right next to you, too?"

The child was shaking his head, lost in thought. He put a twig into the tap, spraying the water onto fat, overripe cucumbers, resembling piglets.

She took his hand and guided him, stunned by the sun and the miraculous knowledge, down the field path, between unending rows of tomato plants, heavy with their red fruit.

He dragged his feet through the dust, thoughtfully watching the clouds around his knees.

The woman held back her laughter: "Children are always, always, born to mommies. And not from soft-boiled eggs. You were born from an egg which was a gift from your dad. Because at the very beginning there has to be a mom and a dad and they have to be good to each other, so that the child will come into a proper family. So that they love him, and look after him till he grows up."

He picked a pea-pod off the vine, split it open and had an idea: "Mom, since I grew in you, I am like your little pea. And the other one will be a second pea. And when there is five of us, you will be like the pod and we will be your peas."

He picked out the peas, poured them onto his tongue and mouth full, said: "We grew in you, so we really are all yours, even the new Kulka. I will lend him everything then. Even my skates!"

The woman smiled, but only inwardly, softly, as mothers do. From the field the women called out: "Mrs. Kulka, how soon now?"

And at him: "A stork will bring you a little sister!"

He looked around, and full of the secret knowledge he whispered: "They don't know? Too bad for them." And he added, "Our child really should have the most beautiful name ever. If it is a brother, he should be Gooseberry. And a sister could be Radish."

The sun reflected in the greenhouses as if they were huge diamonds thrown into the rich loam. The young woman supervisor came out with a basket of strawberries: "Come have some, Mrs. Kulka. They are so sweet, just smell them."

The woman took a strawberry, placed it in the boy's mouth. "Such heat," she said. "Like before harvest."

The earth resounded with ripening and the insistent trilling of crickets.