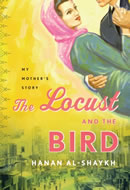

Hanan Al-Shayk, a Lebanese writer who has apparently shied away from very little during her literary career, has written perhaps her most intimate, and most cathartic, book to date. Famed for her frank examinations of women's sexuality in Arab societies, her books often read as appeals for understanding and openness in discussing otherwise taboo subjects. However, it seems that there was one particular Arab woman to whom Al-Shayk herself could not extend the same understanding: her mother Kamila. The Locust and the Bird was written to right this wrong.

In telling her mother's story, Al-Shayk bravely attempts to exorcise some of her own demons by looking at the lives that spawned them. She was unable for most of her life to see her mother as anything other than the woman who abandoned her young family for her lover; then, in Kamila's declining years, her daughter was persuaded to hear her story. And it is a story worth hearing: born into a dysfunctional family in rural Lebanon, transported to Beirut to separate her from her father, forced into marriage at the age of thirteen, illiterate her whole life. Kamila is robbed of her childhood, only to emerge as a strangely childlike adult. It is, for instance, only after she falls pregnant for the second time that the facts of life are explained to her. As she grows, she develops a hardness and manipulative edge that allows her to maximise what she can get out of her domestic situation, even as it breaks her heart to see what she has become. The only ray of hope is her lover Muhammad—the man who will ultimately destroy her relationship with her daughter.

The author's bravery isn't confined to the subject matter. Kamila's story

is told using Kamila's voice, and Al-Shayk's usually adept prose is thereby

sacrificed for something more visceral, which sometimes reads more like a

transcript of an audio recording than well-crafted storytelling. Initially

irritating because of its clumsiness, the plaintive quality of Kamila's

voice lends an honesty that would perhaps have been otherwise absent.

This isn't a novel, and it doesn't feel like one. It may perhaps be a

slightly self-indulgent book, written for Al-Shayk's own peace of mind as

much as for her readers, but it stands as a testament as her skill as a

writer precisely because her own voice is silenced. Skilled in its execution,

courageous in its conception, and richly deserving of praise, Al-Shayk's

latest book is a worthy departure for one of the Middle East's best-known

contemporary voices.

Bloomsbury (UK), hardcover, 9780747599883 , £14.99

Pantheon (US & CAN), hardcover, 9780307378200, $24.95 US, $28.95 CAN

Allen & Unwin (AU), paperback, 9781408800072, $32.99