Published with permission. © Interlink Books, 2011

"Sweetheart."

"My sweetheart."

"My sweetheart."

"My sweetheart."

"When can I see you?"

"I miss you."

"When can we meet?"

"Just come."

"Do you miss me?"

Then, "Are your breasts getting bigger?"

And then, "How's the baby?"

"The bastard. What kind of man doesn't love his own son? Even a dog feels something for its young. He's worse than a dog."

"The bastard broke the phone? That's the third time. I'll get you a new one."

"No, I don't have one."

"I'm telling you I don't have one. It was stolen and the bank couldn't do anything, so I canceled it."

"No, I don't have one, don't you understand?"

"That's enough, Shahinaz, no, no, I'm telling you, no! I don't have one."

"Alright, I've got to go now. I'll see you tomorrow. Leave your car downtown, and we'll go from there together. Alright? Alright?"

That was my father whispering into the phone outside my closed bedroom door.

I listened to him whispering with a tenderness I'd never heard before. Meanwhile, I was trying to keep my breaths as short as possible, as my chest hurt each time I took in air. He sounded tender and sweet. Where had he gotten this voice from, and when did he learn it, if he'd never used it before in his life?

I could hear my father talking about breasts as if he were discussing shares rising on the stock market.

He doesn't even know the way to the sea. Yet he seems to know that a woman's breasts get bigger when she's pregnant.

Trapped behind the closed door by my illness, and forced to listen to his conversation, I was as powerless to control my rising temperature as I was to resist the arousing sensation his explicit words had on my body. I followed this sensation as it spread through me carelessly, until his question about the baby brought me back to my senses. I was frightened. But I instantly realized that my fear of a potential brother related to purely practical concerns: the possibility of having to split our future inheritance with a fourth person, who might even take the largest share of my father's money. After all, his mother had been able to bring out a tenderness in my father that my mother, brother, sister, and I had failed to extract from him over all these years. However, this fear vanished, leaving only pain, the moment I heard him mention another man. I realized that it was not my dad who was the baby's father; it was this other man, the one who had broken the phone three times and was even worse than a dog.

The conversation about the bank card returned me to a sickly calm. For all his explicit, loving words, he was still as stingy as ever. Then, when he started to lose patience towards the end of the call, he was my father again. He never had the energy to listen to any of us. And now she had become one of us.

He hung up and left. A familiar cold silence returned to fill the house once more.

But he had seen enough Egyptian soap operas to know well that she was not his sweetheart and he was not her sweetheart, so how could he have fallen into this trap?

But I too had seen enough soap operas, so what if the baby were my brother and even looked like me? What would I do with a brother like that? In reality, I'd always felt a close affinity with all the wretched of the earth, be they thieves, whores, or tramps. But now that it was no longer an affinity based on mere theory but on reality, in which I was connected with a brother who shared a father with me, I felt utter revulsion for the wretched Shahinaz. So I wouldn't go with her to the hospital for the delivery, and I wouldn't stand in the corridor listening to her scream as she gave birth to my half-brother. I didn't even know, if I had the choice, whether I would choose that this child should be born or not. I didn't know either if I would like to take this potential brother to the zoo, or out into the country. He'd pick a flower, push it in his mouth, then spit it back out, staring up at me with tearful eyes that betrayed its horrible taste—eyes that might resemble my own, inherited from my father. No.

I slept, then woke to a feeling of cold. My hair and my forehead were wet with sweat, and my eyes and face were wet with tears.

My father.

The first drop of tears fell onto the pillow reluctantly, but those that followed fell with extraordinary ease, settling together in one damp spot, which began by my cheeks and spread out to the sides. At first, the damp pillow was a little warm, but after a few moments it turned cold, painfully cold, so I turned my head in the other direction to avoid it. The tears now changed course and started to trickle from the corners of the eyes across the nose, before sloping diagonally along the cheek, falling into the ear and a moment later onto the pillow. I was tired. I felt heavy and irritated by my tears, though they had now begun to slow.

Outside, it was raining. I followed the raindrops' flow on the window screen. Like the tears, each new drop landed in the same spot and followed the path carved for it by the preceding one. Each drop was separated from the next by only a few small squares as it made its way through the mesh, until it reached the bottom of the window. How did each drop manage to land on the screen in the very same spot that the first drop had chosen? The interval between the raindrops was the same as that between my tears. I wasn't imagining this. I hadn't imagined the conversation on the other side of the door.

I was convulsed by tears, they burned my face, making me want to tear at it. I didn't want to lose my mind, I wasn't mad, how could I hold on to my senses?

I slept again.

There was the coldness of the sweat beneath me, and the coldness of the tears on the pillow. I remember that I cried. I remember the conversation.

The sound of the Syrian soap on the television could just be heard through the patter of the raindrops. If the television hadn't been on, the patter of the rain would have been the only sound audible as background to my sadness.

Suddenly, the door of the room opened. It was my father.

He opened the wardrobe, which was no longer my own wardrobe since I had left home. He and my mother had put things in it that had nothing to do with each other or with anyone at all.

I looked back up at the ceiling. I knew from the noise that what he had taken out of the wardrobe must be sweets, most likely peppermints. No one likes peppermints; that's why he would put them within reach of everyone's hands, knowing no one would ever reach for them. He asked me if I'd like one but I didn't reply.

He stopped for a moment and asked how long I would be staying in bed without consulting a doctor. Again, I didn't reply, and he didn't wait for my reply, and didn't shut the door behind him either.

From time to time a shudder went through my back. It started from the bottom, then spread in circles until it covered it all. I wanted to die, and felt cold and hungry. I hadn't eaten anything since the previous day.

If it hadn't been for what had happened, I would have taken a peppermint from him, instead of the taste of sickness that filled my mouth.

He was now leaning on the wall by the door frame, looking at the television, his head in front of me and his arms around his head, while I was thinking what a filthy man he was.

In the morning, he had been an incredible man.

Until that morning, I would sometimes find myself crying because it had occurred to me that he might die. A terrible weakness would overcome me, anticipating the sadness that I knew would inevitably crush me as soon as he died. Several times I had thought of killing myself to escape from this likely tragedy, and I actually tried to do so at least twice. This same pillow that was underneath me now, damp from my tears after the morning's conversation, had been soaked in the past with tears of another kind: tears at the thought of his possible death. How terrified I was at the thought of living without him, without the knowledge that he was still alive somewhere or other. And now I suddenly could, or perhaps it no longer bothered me.

Where had these feelings come from all of a sudden? From one telephone conversation that had lasted two minutes at most, of the total time in the universe. It probably hadn't even reached the minimum length for a call, which would cost less than the smallest peppermint in the cheapest shop. Still, it had made that deep, great, powerful, conquering—and all the rest of the traits of the Almighty—love disappear.

This was the first time I had noticed that he was so old. His hair was thinning, and was almost entirely white, and he had wrinkles all over his neck and hands.

I woke up and found the door of the room closed. I didn't know who had closed it. I stretched out my hand to my genitals and started to masturbate quietly. Then I moved my hand back to my nose, and the smell stirred tears in my eyes.

Go on, cry.

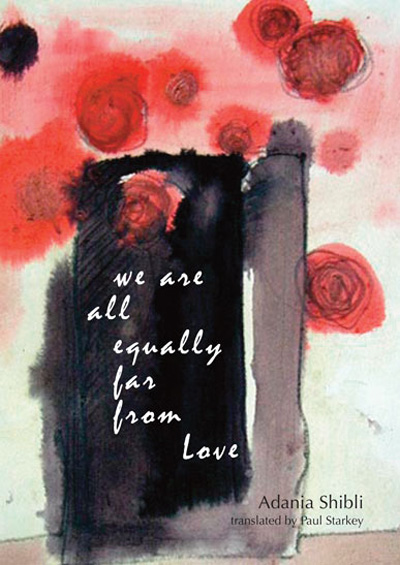

Adania Shibli, born in 1974 in Palestine, is two-time winner of the Qattan Foundation's Young Writer's Award for this and her acclaimed novel Touch. Paul Starkey is head of the Arabic department at Durham University, England. He is the author of Modern Arabic Literature and a prolific translator.

We Are All Equally Far From Love is available in paperback in February (9781566568630) from Interlink Books, or at your local or online bookstore.