Belletrista recently interviewed Professor Michael Naydan about his article-in-progress

concerning the emergence of literature written by Ukrainian women over the last several decades.

Professor Naydan is the Woskob Family Professor of Ukrainian Studies at The Pennsylvania State

University, and is the compiler and co-translater of an anthology of contemporary Ukrainian

women prose writers. Professor Naydan is also the author of an article-in-progress about the

emergence of literature written by Ukrainian women over the last several decades. We had the pleasure to read

a draft of the article.

Professor Naydan, in your article you mention a "conspicuous blossoming" of female prose writers in Ukraine that began in the last few decades of the 20th century. Can you tell us a bit about this "blossoming" and why you think it might have occurred at this particular time?

Women to a great degree have been on the periphery of Ukrainian culture during Tsarist times as well as during the Soviet period. Much of this had to do with the tenor of the times and gender stereotypes in the 19th century, but even in the 20th century, the Soviet system, despite lip service to equality of the genders and constitutional guarantees, remained archconservative and backward. While there were several Ukrainian women poets of note in the 20th century (Lesya Ukrainka, Olena Teliha and Lina Kostenko for example), only one Ukrainian woman prose writer of considerable acclaim appeared before the 1980s—Olha Kobylianska in the early part of the century. Teliha was executed by the Nazis at Babyn Yar, and Kostenko underwent over a decade of publication silence during Soviet times. One other major woman writer appeared in the emigration—Emma Andijewska, who emigrated to Germany and published surrealistic prose works, though she's actually best known as a poet and artist.

The conspicuous emergence of Ukrainian women writers began at the beginning of glasnost in the USSR in the mid-1980s, during a time of the lessening of state controls over literature and the lifting of restrictions on travel abroad. While this renaissance started in the area of poetry (Natalka Bilotserkivets, Oksana Zabuzhko, and Ludmyla Taran to name a few from the 1980s generation of women poets), it rapidly expanded to prose over time. Halyna Pahutiak and Evhenia Kononenko began publishing their prose works then. Kononenko's depictions of characters in dysfunctional family situations in her intensely realistic prose works couldn't have been possible before then when the requirements of Socialist Realism demanded that a positive spin always be placed on Soviet reality by writers. Additionally, during that transitional period, younger women writers began to travel and had the opportunity to communicate with their counterparts abroad, and, at the same time, foreign visitors began to come more regularly to Soviet Ukraine. This generated mutual dialogue and sparked an interest among Ukrainian women writers in expressing themselves and realizing their potential. This urge to discover the West expanded even more dramatically after Ukrainian independence in 1991. Oksana Zabuzhzo and Solomea Pavlychko were among the first younger generation scholars to travel abroad to the US. Pavlychko, a literary scholar, who translated the poetry of Emily Dickenson into Ukrainian, became one of Ukraine's first active feminists and started the Osnovy Publishing House. She, unfortunately, tragically died in an accident in her home on New Year's Eve at the end of 1999.

I was actually present at the moment of the birth of the idea for Oksana Zabuzhko's first novel. I was

head of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature at Penn State when I invited Oksana to be a

Fulbright scholar at my university during the summer of 1995. Following a bitter love relationship with

a Ukrainian artist that ended catastrophically, Oksana began to relate to my administrative assistant

Linda the miseries Oksana endured during her failed relationship. I caught the end of their conversation

in our department office when Linda said to Oksana: "You should write about it, Oksana." Oksana, in fact,

took the cue and did begin to write about it shortly thereafter, and started to pen her prose work Field

Work in Ukrainian Sex, which functioned as self-therapy for her to bring her out of her depressed emotional

state. The publication of Zabuzhko's book and the uproar surrounding it, pro and contra, in the press and

in Ukrainian society in general, seemed to act as a catalyst for other women writers. They had their

stories, too, and something to say.

I was actually present at the moment of the birth of the idea for Oksana Zabuzhko's first novel. I was

head of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature at Penn State when I invited Oksana to be a

Fulbright scholar at my university during the summer of 1995. Following a bitter love relationship with

a Ukrainian artist that ended catastrophically, Oksana began to relate to my administrative assistant

Linda the miseries Oksana endured during her failed relationship. I caught the end of their conversation

in our department office when Linda said to Oksana: "You should write about it, Oksana." Oksana, in fact,

took the cue and did begin to write about it shortly thereafter, and started to pen her prose work Field

Work in Ukrainian Sex, which functioned as self-therapy for her to bring her out of her depressed emotional

state. The publication of Zabuzhko's book and the uproar surrounding it, pro and contra, in the press and

in Ukrainian society in general, seemed to act as a catalyst for other women writers. They had their

stories, too, and something to say.

I think that once other younger women authors saw there was an audience for women's writing and there were no impediments to stop them from writing, they took to their pens and later their keyboards. Many of the younger women writers along with a few from the older generation already had careers in print or media journalism, so writing was already a significant part of their lives. Over the past decade the Internet has also helped to democratize the publication process, giving more opportunities for writers to share their works online. The West-East literary website, which is operated by three women authors (Oksana Lushchevska in the US, Tetyana Melnyk in Germany, and Dana Rudyk in Poland), is one good example of many: http://www.zahid-shid.net/.

Is this "blossoming" limited to just a few kinds of prose, or does it encompass a wide range of literature? Are young writers driving these developments or is it women of many ages?

The prose being written today is of an extraordinarily wide variety. Evhenia Kononenko mostly writes in the mode of extreme realism; Oksana Zabuzhko in a highly complex, philosophical way for an intellectual audience; Halyna Pahutiak in the vein of magical realism, fusing historical reality with myth. Svitlana Pyrkalo, Irena Karpa and Sophia Andrukhovych candidly depict their personal experiences in a confessional modality; Dzvinka Matiyash writes highly philosophical and reflective prose. In the prolific prose of Iren Rozdobudko one finds popular mystery novels in a highly accessible style. In Maria Matios' works, the author often focuses on her own roots in the Bukovyna region of Ukraine with colorful local characters, who speak the local dialect. One of the youngest authors, Tanya Malyarchuk, writes in a minimalist, light style, but experiments with different types of narrative, often even taking a male perspective. Liuko Dashvar, the pseudonym of Irina Chernova, who began writing in her fifties, might be the best selling of all the current women authors with her highly popular realistic novels on village life in southern Ukraine. One can find lots of sex, drugs and rock and roll, to borrow a cliché, among the younger authors too. So there is really a bit of everything from mature writers in their fifties to younger ones in their twenties, from high brow to low brow. The appearance of such a number of women writers is quite a natural evolutionary trend following the breakup of the USSR. Women are by nature wired to be verbally communicative. It was really only a question of time in this day and age when Ukrainian women would begin to fulfill their potential as writers.

Can you introduce us to a few of the significant women who are writing in Ukraine today and tell us a little about the kinds of books they are writing?

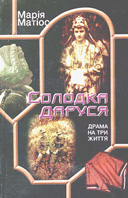

I usually don't like to make strict hierarchies, so I'll just mention a few of the writers who are the most interesting from my perspective. Tastes of course always differ, and I have my favorites (mostly the ones I translate). One can't help but mention Oksana Zabuzhko. She is one of the leading Ukrainian women writers and in many ways a pioneer, though the complexity of her writing style in her fiction, literary criticism and philosophical works tends to be geared toward a high-brow audience. Her Field Work in Ukrainian Sex (1996) received an award for best autobiographical work shortly after it was published, and it does, in fact, blur the distinction between fiction and non-fiction. Her books in the style of new journalism such as Let My People Go (2005) that chronicles events of the Orange Revolution are more accessible for a wider audience. Her most recent book Museum of Abandoned Secrets (2010) has elicited mixed reactions: positive for its high degree of intellectuality, negative for its stylistic complexity, dryness and length. The author's "I" virtually always tends to be the hero of all of Zabuzhko's works of fiction, which are an exploration of herself by herself even under the guise of other characters. Maria Matios is another author of note in contemporary Ukrainian women's fiction. Her novel Sweet Darusya, part of a trilogy that reconstructs elements of her childhood past in Bukovyna, which is located in the part of Ukraine bordering Romania, is considered by many to be her crowning achievement. I often compare the book to Toni Morrison's Beloved in the way that Matios lets the characters tell the story on their own terms through their own voices in their own dialect in their indigenous village. In the novel Matios presents an exquisite portrait of the main character Darusya, a local village girl considered crazy by the local inhabitants for her eccentric behavior, but who harms no one and who just tries to live the life she has been given. The novel in its later parts retrospectively reveals the reasons for Darusya's behavior through the depiction of the traumatic events she and her family experienced during the Bolshevik takeover of the region. Matios is somewhat of a late bloomer as a prose writer, but has become extraordinarily prolific over the past decade. There is not enough space here to discuss all the emerging writers of note, but I did want to single out the prose of Tanya Malyarchuk, one of whose stories is in this issue of Belletrista. The author of six books at the relatively young age of 28, Malyarchuk is a writer wise beyond her years and life experiences. She often presents slice-of-life vignettes of peoples' lives in Ukraine from different perspectives and with gentle irony. Her writing style is terse and compact, yet packed with deep psychological understanding. She tackles both urban themes and village life in her prose. She tells the story of a city dweller numbed by the government bureaucracy in "Canis Lupus Familiaris." His mental breakdown that leads to him behaving like a canine reminds me a bit of Nikolai Gogol's "Diary of a Madman" and "The Overcoat." Malyarchuk also explores childhood and a childhood perspective in rural settings in stories such as "A Village and its Witches," which is one of my favorites.

Are there particular difficulties faced by women writing in Ukraine today? I understand that one of the writers you profile in your research has been persecuted by the police.

There still is relative freedom for women writers and women journalists to write in today's Ukraine, but that freedom has been threatened by the new authoritarian Yanukovych government on several occasions over the past year. Ukrainian women journalists and intellectuals have largely been critical of the Yanukovych regime for its attempts to stifle free speech and to revert the Ukrainian educational system to a neo-Soviet one. Maria Matios' publishing house was ransacked by government agents, who sought to confiscate copies of her recent book of memoirs, in which she called the monument to the "Great Patriotic War" (World War II) in Kyiv a giant phallus. Virtually everyone I know in Ukraine describes the grotesque outsized titanium statue of a woman with a sword in similar ways. To her credit, Ms. Matios fought back by publicizing the actions in open letters published in the press. Many women journalists are leading the criticism of the Yanukovych government for its anti-democratic activities. So, I'm sorry to say, the future may hold great dangers for them, but hopefully the tide turns toward the direction of democracy. There always, of course, is danger in every act of courage.

Has the work of many contemporary Ukrainian female writers been translated and published in English? If not, why do you think that is?

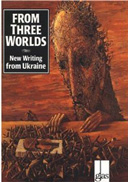

The Zephyr Press volume From Three Worlds: New Writing from Ukraine (Boston, 1996) contained

translations of two stories translated by me: Evhenia Kononenko's "Three Worlds" and Halyna Pahutiak's

"To Find Yourself in a Garden." The volume, edited by Ed Hogan with guest editors Askold Melnyczyuk,

Oksana Zabuzhko, Mykola Riabchuk and me, included a general introduction on new Ukrainian literature

by Solomea Pavlychko. Very few women prose writers were publishing at the time, and it was difficult

then to find more quality women authors for inclusion in the volume. In the Coteau Books volume

Two Lands, New Visions: Stories from Canada and Ukraine (Saskatchewan, 1998) one can find four

translations of Ukrainian women writers in Marco Carynnyk's and Marta Horban's translations:

Oksana Zabuzhko's "I, Milena," Evhenia Kononenko's "An Elegy about Old Age," Svitlana Kasianova's

"Cold Medicine," and Roksana Kharchuk's "Always a Leader." The story "I, Milena" was republished

in the Northwestern University Press edition The Third Shore. Women's Fiction from East Central

Europe (Evanston, 2006). Askold Melnyczuk has translated Oksana Zabuzhko's story "Girls" for Words

without Borders online (see link below). Halyna Hryn published a translation of an excerpt from

Zabuzhko's Field Work in Ukrainian Sex in the journal AGNI. That is available online along with an

interview with the author about the novel (see links below). The complete novel will be coming out

shortly in Hryn's translation with Amazon (see link below). In 2009 the British Council supported

the publication of Half A Breath: A Brief Anthology of Young Ukrainian Writers (Teka Publishers)

that included excerpts of translations from the prose of Irena Karpa and Kateryna Khinkulova as

well as the prose of Svitlana Pyrkalo under the title "Good-Bye, Brezhnev." My translation of

Tanya Malyarchuk's short story "A Village and its Witches" appeared in Hayden's Ferry Review

(Spring 2009). Another of my translations of her prose, "A Woman and Her Fish," just appeared

in volume 194 of the British journal Stand. And a third story in my translation is online at the

European Literature Days festival website (see link below). My translation of an excerpt of

Maria Matios' novel Sweet Darusya will be coming out in the spring 2012 issue of the journal

Metamorphoses, and another translation of the first chapter of Halyna Pahutiak's novel The Minion

from Dobromyl will appear in the same issue. A few women writers (Emma Andijewska, Evhenia Kononenko

and Iryna Vilde) can be found in translation in the online literary journal

The Zephyr Press volume From Three Worlds: New Writing from Ukraine (Boston, 1996) contained

translations of two stories translated by me: Evhenia Kononenko's "Three Worlds" and Halyna Pahutiak's

"To Find Yourself in a Garden." The volume, edited by Ed Hogan with guest editors Askold Melnyczyuk,

Oksana Zabuzhko, Mykola Riabchuk and me, included a general introduction on new Ukrainian literature

by Solomea Pavlychko. Very few women prose writers were publishing at the time, and it was difficult

then to find more quality women authors for inclusion in the volume. In the Coteau Books volume

Two Lands, New Visions: Stories from Canada and Ukraine (Saskatchewan, 1998) one can find four

translations of Ukrainian women writers in Marco Carynnyk's and Marta Horban's translations:

Oksana Zabuzhko's "I, Milena," Evhenia Kononenko's "An Elegy about Old Age," Svitlana Kasianova's

"Cold Medicine," and Roksana Kharchuk's "Always a Leader." The story "I, Milena" was republished

in the Northwestern University Press edition The Third Shore. Women's Fiction from East Central

Europe (Evanston, 2006). Askold Melnyczuk has translated Oksana Zabuzhko's story "Girls" for Words

without Borders online (see link below). Halyna Hryn published a translation of an excerpt from

Zabuzhko's Field Work in Ukrainian Sex in the journal AGNI. That is available online along with an

interview with the author about the novel (see links below). The complete novel will be coming out

shortly in Hryn's translation with Amazon (see link below). In 2009 the British Council supported

the publication of Half A Breath: A Brief Anthology of Young Ukrainian Writers (Teka Publishers)

that included excerpts of translations from the prose of Irena Karpa and Kateryna Khinkulova as

well as the prose of Svitlana Pyrkalo under the title "Good-Bye, Brezhnev." My translation of

Tanya Malyarchuk's short story "A Village and its Witches" appeared in Hayden's Ferry Review

(Spring 2009). Another of my translations of her prose, "A Woman and Her Fish," just appeared

in volume 194 of the British journal Stand. And a third story in my translation is online at the

European Literature Days festival website (see link below). My translation of an excerpt of

Maria Matios' novel Sweet Darusya will be coming out in the spring 2012 issue of the journal

Metamorphoses, and another translation of the first chapter of Halyna Pahutiak's novel The Minion

from Dobromyl will appear in the same issue. A few women writers (Emma Andijewska, Evhenia Kononenko

and Iryna Vilde) can be found in translation in the online literary journal

LINKS TO WORKS IN TRANSLATION

Oksana Zabuzhko's novel Fieldwork in Ukranian Sex on Amazon.

The page contains an interview with the author.

A chapter of Field Work in Ukrainian Sex available online from AGNI.

A conversation with Zabuzhko regarding her novel:

Askold Melnyczuk's translation of Zabuzhko's story "Girls" online:

Tanya Malyarchuk's story "The Demon of Hunger" can be downloaded from the archive of the

European Literature Days website here

(it's on pages 40-42 of the downloadable pdf file of translations. Click the download button for

"All readings at the European Literature Days 2010"

Volume 1 (2004) of Ukrainian Literature: A Journal of Translations is available for

downloading here (translations of Evhenia

Kononenko's "On Sunday Morning" translated by Svitlana Kobets, and selections from Emma Andijewska's

Tigers)

Volume 2 of Ukrainian Literature: A Journal of Translations is available for downloading

here (translations by Uliana Pasicznyk of

Emma Andijewska's "Tale about the Vampireling Who Fed on Human Will" and "Tale about the Man Who

Knew Doubt" along with Khrystyna Bednarchyk's translation of Iryna Vilde's "Three Miniatures")

WEBSITES OF UKRAINIAN AUTHORS

Larysa Denysenko's website.

Irena Karpa's website

Evhenia Kononenko's blogsite.

Maria Matios' website

Svitlana Pyrkalo's website

Iren Rozdobudko's author's page.

Oksana Zabuzhko's website