Annabel is the story of a baby born with both male

and female genitalia, in 1968, in a remote village in Labrador, an isolated region of Canada. A decision

was made, somewhat reluctantly by the baby's mother and her best friend (also the midwife), to raise the

child as a male and so his vagina was stitched shut. He was given life-long medication and the female

side of Wayne was hidden inside himself. By the time he reaches puberty though, it is clear to Wayne that

he is not like other children; and so the truth is revealed to him in bits and pieces. More than just a

story of what it's like to live an intersex life, this is a story of silences and secrets, and about

identity and how we all perform our genders.

Annabel is the story of a baby born with both male

and female genitalia, in 1968, in a remote village in Labrador, an isolated region of Canada. A decision

was made, somewhat reluctantly by the baby's mother and her best friend (also the midwife), to raise the

child as a male and so his vagina was stitched shut. He was given life-long medication and the female

side of Wayne was hidden inside himself. By the time he reaches puberty though, it is clear to Wayne that

he is not like other children; and so the truth is revealed to him in bits and pieces. More than just a

story of what it's like to live an intersex life, this is a story of silences and secrets, and about

identity and how we all perform our genders.

Annabel was nominated for the three top Canadian literary awards: The Scotiabank Giller Prize

(shortlist), the Governor General's Award, and the Roger's Writer's Trust Fiction Prize. It is also

currently shortlisted for the Orange Prize 2011.

Please join three Belletrista readers in their discussion of this intriguing book.

Participating:

Cyrel, 63, retired art teacher and artist, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Darryl, 50, pediatrician in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Joyce, 47, Corporate writer & editor in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Joyce: Although I didn't think that Annabel was the perfect book, I really enjoyed it. In fact, when I read it last autumn, I thought it was one of the better books I'd read all year. I found it interesting, beautifully written, and unique. Winter writes with elegant simplicity, and I thought she approached her characters with great dignity and sensitivity. What were your overall impressions of the book?

Cyrel: I was very touched by this book. In fact, I cried when I finished reading it. I found it to be a powerful story about love between these two very different parents and their child. The book was also about survival in a harsh world. I also liked Winter's writing style. She created plot twists that led me to change my mind many times about my feelings for the characters.

Darryl: My impression of the book was greatly affected by what I perceived to be medical misinformation about hermaphroditism. For the moment, I'll say that I enjoyed the story and its characters, and its setting in a culturally isolated town where people did not tolerate differences from the norm. However, I found some of the decisions made by the key characters difficult to believe, and several events that occurred were quite implausible, in my opinion.

Joyce: Darryl, you brought up the term hermaphrodite, which has prompted a question. Winter uses this term in the novel. This is something I know almost nothing about, so while reading the book I searched the Internet for some information. I quickly learned that when referring to humans, the term "hermaphrodite" is frowned up and even considered to be stigmatizing. The correct term in 2011 is "intersex". Putting aside the discussion of medical accuracy, I find it odd that Winter chose to use a politically incorrect term in a novel that is otherwise so sensitive and thoughtful. Do you know why she would use that particular label?

Darryl: You are right, Joyce. The terms "hermaphroditism" and "intersex disorders" have been replaced by "disorders of sexual development"; the previous terms were both misleading and stigmatizing. I'm pretty sure that, in 1968, when Wayne was born "hermaphrodite" would have been used by clinicians to describe his disorder, so I can understand why she used the term.

Joyce: When I was reading the book, the use of that word struck me as odd. I see what you mean though, and I agree with your explanation. However, since it has a third-person narrator, I expect that an author will somehow explain why she isn't using the currently acceptable term. I think this ties back in with your problem with the inaccuracies in this book, and our expectations of accuracy as readers.

Cyrel: Without any knowledge of current terminology, I think Winter uses "hermaphrodite" because it may be familiar to the reading public.

Darryl: I don't have a problem at all with Winter's choice of the term "hermaphrodite" in the book,

or her decision not to define the term for a 21st century audience of readers. In my opinion, authors

should stick with the medical terminology and state of knowledge that applies at the time the narrative

takes place, and should not feel obligated to provide up-to-date information for their readers. For

example, if I decide to write a novel about the onset of HIV in the early 1980s, I would use the term

GRID, or gay-related immune disease, instead of HIV/AIDS, as that term was in use from that time until

the mid 1980s, although it is a stigmatizing and demeaning one.

Cyrel: I believe that one of the themes of this book is that of choices that parents make for their children, and the consequences of those choices. Do either of you care to comment on this?

Darryl: I agree that parental choices and their consequences was one of the book's major themes, starting with Jacinta's decision not to inform Treadway of the baby's ambiguous genitalia, and Treadway's unilateral decision to determine that the baby would be raised as a boy. These decisions were implausible to me, and neither would occur in 2011.

I also thought that personal choices and their consequences was another theme: Thomasina's decision to bring Wayne to the hospital after she learned of his abdominal swelling, without gaining the consent of his parents; Wayne's decision to stop his hormonal therapy when he lived in St. John's; Wayne's decision to tell an immature teenager (Steve Keating) about his condition, which resulted in him getting beaten by a gang of thugs.

Cyrel: The choices that Treadway, Jacinta and Wayne made impacted not only on themselves but on others as well. For me, one of the central incidents was the dismantling of the bridge structure by Treadway. I found Wayne's reaction to the destruction of his bridge very passive. Treadway was trying to shape the way his child behaved; he had a whole program of chores laid out for the boy. Did this negate Wayne's interests that his mother encouraged? Certainly this action and the loss of the music so valued by Wally made a difference in Wayne’s action. I did find Wayne's reaction to the destruction of his bridge very passive.

I also believe that isolation was an important theme in this book. The characters all had an inner life that really was not shared with others. Labrador and the small community provided the external isolation. But it was what I perceive as the internal loneliness that gave this book its resonance for me. What do you think?

Darryl: I agree. And now that you mention it, I think that was the book's main strength. I was especially touched, and saddened, by the inability of Wally and Wayne, Jacinta and Treadway, and Wayne and both Jacinta and Treadway to discuss their relationships in a meaningful fashion. It seemed as though the closer the relationship between two characters (husband and wife, son and parents, etc.), the less likely they were to establish a meaningful connection with each other.

Joyce: Yes, the isolation was definitely an important factor. On a simple level, Kathleen Winter

is from Newfoundland, so it seems an obvious setting. And I think it's a conventional society in which

to set the story and use as a contrast—this would be an entirely different story if it were set in

Toronto, or New York, or London. Labrador is a remote part of Newfoundland, which is a remote part of

Canada, which is a country often considered remote from the rest of the world. Newfoundland is sort of

like Tasmania or Patagonia. But on a more complex level, I think it's symbolic of the isolation each

character feels in his or her own life.

Darryl: Throughout the book I found myself thinking or openly exclaiming "Wait … what???" after reading about a significant event: Wayne's self-fertilization, which resulted in the fetus that was found on the exploratory surgery for the blood in his womb (this is impossible); the shard of glass that Wally inhaled, which lacerated her vocal cord (extraordinarily unlikely, if not impossible); the operation on Wayne as described above (this was performed without the signed consent of a parent?). These implausible events ultimately ruined the novel for me. I assume that my medical background (and the author's lack thereof) affected my enjoyment of the book. Did either of you find similar passages that did not ring true, or seemed unbelievable?

Joyce: I had actually forgotten about the self-fertilization. I think that means I may have dismissed it. I certainly would have raised my eyebrows at that one! After all, we're talking about humans here, not seahorses (or whatever animal does that).

Darryl: Exactly! Flowering plants, invertebrates, and protozoans can; humans can't!

Joyce: I didn't realize that the glass shard incident was as good as impossible. I thought it was horrific and sad.

Darryl: I think you would have a better chance of winning the Mega Millions Lottery five times in a row!

Joyce: When I come across an author getting facts wrong, I quickly lose faith with the author's credibility. Is this fair? Probably not. But it's a pet peeve of mine, especially in historical fiction (potatoes in medieval Europe, people thinking the earth is flat, that sort of thing). I like to learn when I read—even when I read fiction—-and it's important for me to trust that a writer will get the facts right. I know this is unimportant to some other readers.

When my book club read The Da Vinci Code, I ripped it apart because of the vast number of inaccuracies (especially about art history). One of the other members said she just loved the story. I asked her if she wouldn't be irritated to read, "On that sunny Paris afternoon in September, he admired the tulips waving in the breeze," and she said she wouldn't even notice. I, on the other hand, would be tempted to throw the book in the recycling bin.

Darryl: I completely agree, except that I think it is fair to require this of an author and to call her to task when she gets it wrong—if it plays a major role in the story.

Cyrel: Darryl, I want to explain how I felt about the medical information. I am not an expert, so I read those incidents that you describe as "implausible" as horrific medical emergencies. I was more concerned with the behaviour of the characters in relation to them.

For me, the elements that did not ring true were really omissions by the author. I was invested in reading about Wayne's mother and wanted to know more about her feelings and thoughts in the last third of the story.

Joyce: I know! She just disappeared, and I missed her and wondered what had happened to her.

Darryl: I agree!

Cyrel: Darryl, just another thought on the "impossible" incidents that influenced your feelings about this book. Newfoundland has a great tradition of storytelling. In fact, in another Newfoundland author's latest book there is a character, a mute stranger, in the belly of a whale, who washes up on the shore of a small village. (The book is Galore by Michael Crummey.) Perhaps we have to accept some fantastic elements in Winter's book as part of this storytelling history. What do you think?

Darryl: Hmm... I don't mind, and often enjoy stories about unlikely occurrences based on magical realism, myths or folk tales, such as The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso, which centered around a monstrously deformed child born of a mysterious coupling, or Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie, with its specially empowered children.

However, in my opinion, if an author writes about a particular medical condition with specific clinical information, I think it’s important that he or she research the condition thoroughly and get it right— especially if any misinformation becomes important to the story and can mislead the reader. (Humans with disorders of sexual development cannot undergo self-fertilization!) This is of special importance to people who have these conditions, their families, and the clinicians who care for them.

Sorry to be such a curmudgeon about this, but I've read numerous articles and have seen or heard about television programs that misled the public about medical conditions, such as the programs in the US and UK about the purported, and now disproved, link of MMR vaccine to autism that led to the significant decline in childhood vaccination in these countries, and so on.

Joyce: I definitely think there is something to that, Cyrel. Someone suggested to me that some of these implausible events aren't supposed to be real, but are instead more symbolic. I love magic realism and have also read enough folk tales and fiction that is obviously not true, but I don't think this fits into any of those categories. I think when you read those genres, it's fairly clear that it's not meant to seem "real". This is something different … but you might be right in that it's not supposed to be "real" either.

Cyrel: I went online and looked at some reviews of Annabel to see if other readers were as disturbed by the "implausible medical incidents" as you were, Darryl. Some reviewers did use the above term to refer to aspects of the novel. But the characters and themes were the main topics of review.

I thought about what I've read and seen that had unreal aspects, in my area of expertise. I once saw a French film about a teacher and his class that got excellent reviews. While I could appreciate the characters and plot, I thought the teacher exhibited "what not to do" in teaching. So I had mixed feelings about the film.

Darryl: Right, Cyrel. If I knew nothing about disorders of sexual development or medicine, then I almost certainly would not have noticed or been so disturbed by the medical misinformation in the book.

Joyce: Whatever the case may be, I didn't get caught up in any of that because I was so involved in the story. Despite these flaws, the book worked for me.

Darryl: I did enjoy this beautifully written and heartfelt story, and I would hate for my comments

about its flaws to dissuade anyone from reading it.

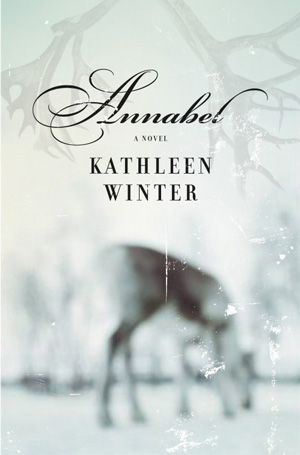

Joyce: I am quite fascinated with book covers and can talk about them almost as much as the books themselves. The Canadian and US versions of this book have very different covers.

I have the Canadian edition and I think it's absolutely gorgeous. With its frosty blue cover, elegant

font and the deer, it looks like a Christmas card. However, I find it rather feminine, and I can see

some male readers not opting for it, based on this (sad though, that is). Further, it looks cold, especially

with the author's name (Winter) right in the middle. Although I find it beautiful, I'm not sure that it

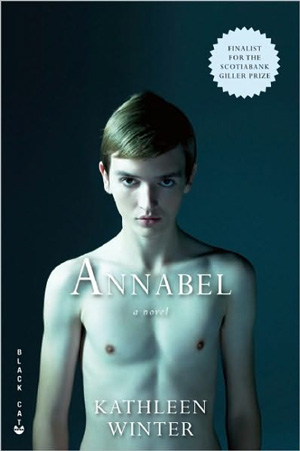

represents the novel very well. I also recently saw the US & UK edition, and I suppose this one more

accurately represents the subject of the book. The title is a female name, but the figure is male, so

that's good, I think. The way the picture is lit, though, looks a little sinister and Wayne/Annabel isn't

sinister in the least. I can't say I like this cover much; it just doesn't capture the mood of the story.

I have the Canadian edition and I think it's absolutely gorgeous. With its frosty blue cover, elegant

font and the deer, it looks like a Christmas card. However, I find it rather feminine, and I can see

some male readers not opting for it, based on this (sad though, that is). Further, it looks cold, especially

with the author's name (Winter) right in the middle. Although I find it beautiful, I'm not sure that it

represents the novel very well. I also recently saw the US & UK edition, and I suppose this one more

accurately represents the subject of the book. The title is a female name, but the figure is male, so

that's good, I think. The way the picture is lit, though, looks a little sinister and Wayne/Annabel isn't

sinister in the least. I can't say I like this cover much; it just doesn't capture the mood of the story.

Cyrel: Ahh! I find the US and UK covers creepy!

Darryl: I received a copy of the Canadian edition as a gift, and I have seen the US edition in a local bookstore. I greatly preferred the Canadian cover, which I thought was beautiful and not overly feminine or otherwise off-putting. It wasn't reflective of the contents of the book, but I didn't mind that at all. The US cover, on the other hand, is a bit disturbing, due to the boy's facial expression, and his young age with a bare chest. I would have been a bit reluctant to read the US edition in public, but I would have had no problem with the Canadian cover.

Joyce: Thanks for your thoughts, Darryl. It's good to know that the guy in the group didn't find

the icy blue cover a turn-off. And I completely agree with you about the other cover—I don't think

I'd want to read that in public, either.

Darryl: Did you feel that the novel ended abruptly and prematurely? I wanted to know what happened to Wayne and Wally as individuals, and wanted to know if they would become close friends or lovers.

Cyrel: Actually, I was fine with the ending. I was satisfied that Wally and Wayne seemed to move on with their lives. The story was not tied up neatly. I still wanted to know what Jacinta and Treadway were doing. We, the readers, didn't know what Wayne thought about his dual nature—but that was all right too. It didn't matter. What was important was that Wayne was comfortable in whatever skin he/she wanted to be.

Joyce: I was happy with the ending, too, though I can see what you mean, Darryl. When I was reading, I could tell I had only a few pages remaining, and yet there were still some important threads to tie up. So although one doesn't know what happened to the characters, exactly, I got the sense that everything was going to be all right. So I guess, Darryl, it's up to you. Did you think they became friends or lovers?

Darryl: Friends; but I was hoping that a deeper love between them would develop, given their closeness as kids, and personal similarities.

Joyce: I hadn't decided, but I like your conclusion. That's the one I'm going to believe happened.

Joyce: In the final analysis, Annabel exceeded my expectations. From the description, I thought the book sounded interesting because of the unusual subject and the Newfoundland setting. After I got it, though, it sat on my dresser for quite a few months because of its size. But once I started reading it, I flew though it in just a few days because I was drawn to the story and I found it so readable. Did Annabel meet your expectations?

Darryl: No, it did not. There was too much medical misinformation and too many implausible occurrences, which prevented me from enjoying the narrative as much as I would have liked. Did it meet your expectations, Cyrel?

Cyrel: I believe that this book did meet my expectations. I found it a compelling story about characters and themes of isolation, and a lack of communication.

Joyce: I'm just thinking about what kind of reader would like this book. I would recommend Annabel to the type of reader who enjoys literary fiction. It's no surprise to me that it's been nominated for prominent awards because it fits into those categories nicely. I don't think it's the sort of book that would appeal to a super intellectual.

Darryl: I agree with you, Joyce. It would appeal to a reader who appreciates literary fiction and a solid, straightforward narrative.

Cyrel: I think that readers who don't need a storyline neatly finished at the end of the novel and

those who appreciate character studies would like this book. I have given it as presents, and the response

has been good.

If you'd like to participate in one of our future conversations, send us a note at editor [at] belletrista.com.