Harper Perennial Modern Classics, paperback, 9780060953461

Heinemann, paperback, 9780435901318

Flamingo, paperback, 9780586089248

HarperCollins Canada, paperback, 9780061673740

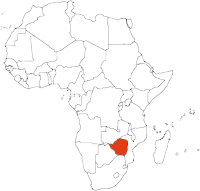

Country: Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia)

The novel opens with the body of murdered Mary Turner. In an inversion of the normal order of

things, that opening chapter tells us not only the ending of the story, but also summarizes

everything we are to experience in the following pages—the "truths", as one character puts

it, behind the "facts" of the case. We see from the beginning that, for all of the apparent official

interest in the murder of a white colonial by a black native, it is almost welcomed by those in power,

for it plugged a gap in the social fictions that colonial society used to maintain itself.

The novel opens with the body of murdered Mary Turner. In an inversion of the normal order of

things, that opening chapter tells us not only the ending of the story, but also summarizes

everything we are to experience in the following pages—the "truths", as one character puts

it, behind the "facts" of the case. We see from the beginning that, for all of the apparent official

interest in the murder of a white colonial by a black native, it is almost welcomed by those in power,

for it plugged a gap in the social fictions that colonial society used to maintain itself.

As a young woman, Mary had put together a life she liked: a job in the city with a bit of money, a wide circle of female and male friends. The latter treated her in a vaguely asexual way which suited her well for she had a strong distaste for even the idea. Then, at age thirty, everything changes when she overhears a conversation between two women talking about the fact that she doesn't quite fit in anymore—is ridiculous, in fact—because she has no husband. In words that leave her aghast they sum her: "She just isn't like that, isn't like that at all. Something missing somewhere." Blindly trying to get back what she has lost, she marries Dick Turner, a poor and ineffectual farmer whom she does not love but is the first man to ask. She follows him to his farm but, once out in the veldt, her life slowly falls apart

The parched land and scorching heat take their toll physically. The loveless marriage (on her part) does not nourish her emotionally. Her pride causes her to refuse overtures from the other women of the region. Most importantly, she is unable to cope with the racial divide. Some outsiders experience it, are revolted by, and leave. The majority slowly accustom themselves, joining ranks in the conspiracy of a "proper" social order. Mary can do neither and tries to suppress her fear of the workers by abusing them. Yet, no matter how much she drives them, even to the point of physical violence, her fear and antipathy continues to grow, consuming her.

The best word I can think of describe the writing during this story is evocative. Lessing makes the reader feel the maddening heat and isolation of the dry season and the sense of intangible menace that Mary experiences. Her characters feel fully formed—so much so that, even as we dislike Mary, we pity her and are dismayed at the path she's on. It's a path that ends in her disintegration with the arrival of Moses: strong, attractive, mission-educated, and possessed of a dignity that refuses to bend its neck. With a horrified fascination we watch as the two of them slip into a double spiral of attraction and loathing that will end with her transgression against the social credo of "her kind", her descent into semi-madness, and Moses standing in police handcuffs.

It's a madness that echoes the communal madness of apartheid, and Mary's role as an extended

metaphor for Rhodesian white society is not subtle. The social certainties that she would be

"better" with a husband are mirrored in the paternalistic certainties of a colonial society that

constantly reassures itself that the natives are much improved by its presence. The fragility

of Mary's control over the workers is emblematic of the fragility of that colonial dominance.

Most of all, her inability to admit of a relationship (however twisted) with a native, even when

it confronts her, is no different from a society whose primary aim was to avoid acknowledging

natives as human. Returning to that first chapter, the defining moment of the book for me is

on page 9, when Charlie Slatter stands looking at the handcuffed Moses with "a kind of triumph,

a guarded vindictiveness, and fear." It's not fear of Moses as a killer, for Charlie is a hard

man himself, well-accustomed to physical violence with natives. It is fear of what Moses

represents: a native who is not subservient, not ignorant, not unaware of the fragility of the

social structure, and not afraid of violence.