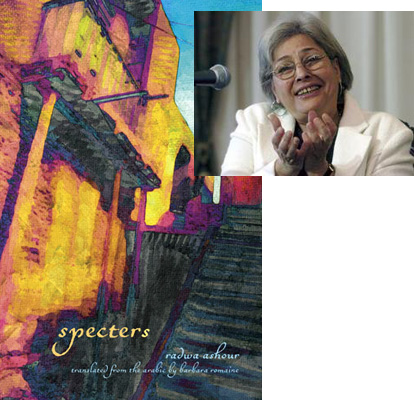

"Radwa Ashour, a highly acclaimed Egyptian writer and scholar, is the author of more than fifteen books of fiction, memoir, and criticism; among them, Siraaj and Granada have been published in English. She is a recipient of the Constantine Cavafy Prize for Literature. She lives in Cairo, where she teaches literature at Ain Shams University, Cairo. She is married to the Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti and is the mother of the poet and political scientist Tamim al-Barghouti.

Specters alternates between the stories of Radwa and Shagar: two women born the same day, one a professor of literature, one of history. The novel that results is part fiction, part autobiography, part oral history, part documentary—a metafiction moving between Radwa, who is writing a novel called Specters, and Shagar, whose has written a history, titled Specters, about the 1948 massacre at Deir Yassin. The novel's structure pays lyrical, compelling tribute to the ideas of the Arab qareen—double or companion, and sometimes demon—and the ancient Egyptian ka, the spirit that is born with and accompanies an individual through life and beyond. Specters unites the projects of history and literature in an evocative, penetrating meditation on the dissolution of boundaries between the personal and the political, on contemporary life in a fractured world." (from the publisher)

Specters won the Cairo International Book Fair Prize.

The valley was full of ghosts. Silent ghosts that tilted with the setting sun to settle in their turn into the depths of the earth, where the shrouded river carried them on boats in its headlong course toward the east. Silence. Then a sound—faint at first and then rising, it would still be echoing in the valley years hence.

She heard only the three that particularly concerned her: her husband and her two brothers. They had gone, and would not return. The door was closed upon their voices, closed tightly and locked with a key secured within her breast. She carried on. She was twenty-five years old, she had two children and a third still in her belly. Six months later she gave birth to a girl.

"I will tend the little ones and my bit of land, and it is no one's business but my own."

Her cousins hated her independence, hated her refusal to marry any of them, and then they hated her capability in managing her own affairs day by day, as if she were not a woman. Even when their anger subsided—the open and the covert hostility—still they kept watching her, waiting out the test of time, to prove to her and to themselves that it was futile to try to break with the customs established by their fathers and grandfathers. She disappointed them. She raised the children, and their needs were met. Still the men's eyes followed her. She was beautiful, and her inaccessibility only made her more appealing. She did not miss out on participating in celebrations and lamentations: she sang at weddings, and at funerals she surpassed the professional mourners, no matter how much they improvised.

"Shagar is stubborn and arrogant!"

"Shagar is strong, above shame!"

They calmed down, and once again made a place for her among them; she accompanied the women carrying jars of water from the river or going to it with their tubs for the washing. Those men who had desired her, or loved her regardless, concealed their desire, pretending to forget it until it seemed, in fact, forgotten.

"A woman equal to ten men!"

This is what they said on the day when the news spread in the village. She neither suppressed the announcement nor revealed any details of what had happened. She said to her first-born son, "Tell your uncles that the girl is dead." They came, saw the body of the slain girl, and they asked, "Who, when, how?" She kept silent. For 40 days not a word fell from her lips, so that they thought she must have been struck dumb. But when her voice returned, she did not speak of the matter. It was as if her nine months of pregnancy and her daughter's fourteen years of life had fallen away, or had never been. She went back to tilling the earth with her two sons, who, like her, were vigorous, strong, and disciplined. Their hard work paid off, and they bought two new parcels of land, then turned around and sold one of them to pay the dowries for two brides.

Shagar danced on the wedding night, then again for the circumcisions of her ten grandchildren. By the time the youngest of them went to the kuttaab, the house—maa shaa'allah—was full of young people, who ploughed the land and sowed it with seed, tended the crops and harvested them, then ploughed once again. Thus in her old age Shagar was left to her leisure, and then the ghosts came to her.

At first the meetings were silent. The ghosts would come in to her, and sit there diffidently mute. Words did not come to her, either. She would steal glances at them, and then, perplexed, go back to staring at her hands. She did not know whether she should greet them and make them welcome as guests—since they had been away— or whether she should leave matters up to them—since the house was theirs and they could conduct themselves in it however they liked, and speak if they wished or otherwise remain silent. As the meetings grew frequent, the intimacy of conversation was gradually restored to them, and so they made up for all the years of separation. Sometimes she questioned them, and sometimes she talked, but most of the time she listened. They had a great deal to say about the forcedlabor trenches at Atabat al-Jisr, about thirst, and about wages never redeemed for bitter toil. All this they had lived and endured over the course of several months. How could this be? She wondered, amazed, for she had lived as best she might, she had married, produced children, been widowed, raised children and grandchildren, and had chafed against the family when they chafed against her. What for her had seemed a full life was, compared to a story like theirs, an insignificant trifle.

She listened. She didn't take her eyes off their faces, or their hands, which clenched and relaxed along with the flow of their speech.When all the family members gathered for dinner and for the cups of tea served afterwards, she repeated for them some of what she had heard. Caught up in her narrative, she did not notice that the children were exchanging glances and holding in their laughter. And if she did hear laughter escaping from one of them, she said, "Stop playing, children. Listen to the story of your grandfathers."

Then her frailty confined her to bed. She could eat only pieces of bread dipped in tea boiled with sugar, following the noon prayer, and this would last her until the same time the following day. The light dimmed from her eyes; she could no longer see more than the shadowy figures of her sons and their children. The ghosts remained, clear as the sun, and they warmed her with their companionship. One day she was taken unawares by the thing she had never expected: they brought her daughter with them—her daughter, whom she had never seen since the day she had beaten her and then found her stretched motionless on the ground.

Shagar gave a shrill cry that terrified the household and the neighbors. They came running. She didn't see them, she didn't hear their questions. She was howling and raking her cheeks. The only thing she saw, standing before her, was her daughter, in whom time had not diminished the slightest detail, from her eyes, her braids, her dress patterned with delicate white flowers, even her breasts just as they had been— time had not filled them out, as if the girl had still not matured.

Shouting and weeping and angry accusations were followed by reproaches and sorrowful exchanges conducted in whispers. They immersed themselves deeply in their mournful talk. Unconsciously, Shagar reached out to her daughter, and they clasped hands.

The daughter did not come and go like the other ghosts. She stayed by her mother's side, keeping her company, not leaving her even when Shagar began to confuse names and her gaze wandered. And then Shagar was gone. Her sons bore her on their shoulders, wrapped in her shroud. The grandchildren followed them, along with the rest of the family and the neighbors. They left the house and proceeded to themosque. They prayed over her. Then they brought her to the cemetery.

"Why 'Shagar'?"

It wasn't a question: it was an abrupt expression

of displeasure. They took it as a question.

"We named you after your great grandmother."

"Your name is Shagar? 'Tree'?" "A tree is big and tall. And besides, it could be a mango tree!"

The second part of the statement was to forestall

objections, for who but an idiot would not

approve of a mango tree?

In the neighbors' garden was a mango tree, a

towering one, whose rough-barked trunk, firmly

rooted in the ground, diverged just like the other

trees into three thick sections, which in turn

sprouted limbs too difficult to count as they appeared

and disappeared amid the dense foliage.

The tree was more than just a pleasant thing to

look at from the nursery window. She craved its

fruit, which she would gather with her eyes when

it was still small, green and hard. She would observe

it as it ripened and plumped. As if outsmarting

her, it only ripened during the days of the

summer holidays: she would hear the thud of the

ripe fruit hitting the ground and she would run to

the window, only to see the neighbors' children

competing for the biggest fruits, the ones that

were the size of two fists put together.When her

father would bring her mangoes, she would eat

her share greedily, her appetite doubled by the

fact that even as she savored the sharp sweet taste

and penetrating fragrance of the fruit, she was

ruled by a craving suspended in the lofty branches

of a tree whose fruit was not hers for the taking.

"Like a mango tree!" she said proudly. The girls moved back and she advanced on them. "Like a mango tree: trunk standing tall, fruit sought by all!"

She won this round at school. At home, though, she could only be reconciled with her name once she knew the story behind it.

It was the locus of a disagreement between the two sides of her family; more to the point, it had supplied an arena for covert wrangling between her paternal grandfather and her maternal grandmother. Her grandfather, Abdel Ghaffar, had made the opening sally.He told Shagar about it. "I suggested that we name you Aziza, but Gulsun Hanim didn't agree, so I said, 'Let's call her Shagar—what do you think of the name Shagar?' At that she seemed even more annoyed. She said, 'If the name must begin with sheen, then let it be Shuaykar or Shukriya.' If she hadn't raised her voice and stuck her nose in the air and strutted around like a turkey… if she had said nicely, 'What would you say to a different name?' then I would have gone along with her wishes. But she pursed her lips and turned her head away as if I'd said, 'Let's call the girl "Dung Beetle."' I lost my temper. I said, 'We're going to call her Shagar, and that's the last word on it.' And your father said, 'By God's blessing, congratulations on Shagar!'"

In the light of these revelations it was easier to interpret that first photograph: Shagar, swaddled in white, nothing showing but her face, with the wide-open eyes and thick black hair just discernible. Sitt Gulsun was holding her on her lap, her arms encircling her, all but enveloping her with her generous bulk. She was frowning, not looking at the infant. She stared straight in front of her, a hint of malice in her expression.Was this because Shagar's grandfather Abdel Ghaffar was standing in front of her and she, looking at the camera, had to look at him, or was she still smarting from the wound she had taken from her defeat in the battle over the name?

Gulsun Hanim did not accept the name, but neither did she refrain from using it. She seized upon it the way an enemy pounces on his opponent's weapon and snatches it away in order to use it against him. With biting sarcasm she emphasized the letter sheen each time she uttered the name "Shagar," vindicated by her own contempt. When did Shagar herself enter the fray? She no longer remembers anything but her automatic alignment with her paternal grandfather's camp. She clung to her name. She barricaded herself behind it. It became the standard that waved over the army to which she belonged.

The no-man's-land between the two camps was no more or less than a long wooden table that separated two chairs: to the right as one entered the house, the chair in which her grandfather Abdel Ghaffar habitually sat, and across from it on the left, the one in which her grandmother Sitt Gulsun sat. Shagar would say, still half asleep, "Good morning, Grandfather. Good morning, Teta." She would go into the bathroom, brush her teeth, wash her face, put on her school uniform, and leave the house in the company of her father, who would take her to school before her parents turned to their daily tasks. As they were leaving, her grandfather would lift his head from his newspaper and say, "Goodbye!" Her grandmother would follow suit, without pausing in her needlework. At four o'clock in the afternoon everyone came home. Her mother would turn the key in the lock and the door would open upon Sitt Gulsun, still absorbed in her embroidery, while her grandfather dozed in the opposite chair. He would be roused by their appearance, open his eyes, and smile.

His powerful memory and robust frame belied his age; only the wrinkles in his face and the dark brown spots on the backs of his hands gave it away.He was a tall man; his awe-inspiring presence was accentuated by the gravity of his darkcolored jubba, which highlighted the shining whiteness of the robe beneath it. These were the clothes he wore when he went out. At home he wore a white jilbab and, over it, in winter, a brown camelhair abaya.

He had an inexhaustible supply of stories about sheikhs and effendis, the Wafd and the king, the English and Saad Pasha, and the wholesale market and those who worked for it. Her father didn't hear these stories; he went back to work in the evenings, and she didn't see him again until the following morning. Her mother didn't hear them, either. Did her maternal grandmother hear them? She couldn't help but hear them as she sat there in the chair opposite, working on her embroidery, but she didn't laugh along with Shagar and her grandfather, nor did she show any sign of emotion when the bullet struck the youth in the chest, killing him, and his companions took him up and carried him, shouting, "Long live Egypt!"

To begin with, Sitt Gulsun produced three pieces, which were mounted on wooden frames: pastoral scenes—men and women clad like royalty in old-fashioned European garments, herding their sheep in fields adorned with flowers. She hung the pictures, displayed in gilt frames, in the parlor. Then she became set on changing the fabric of the chairs, so that she could replace it with the new needlepoint she had done: once again, shepherd-princes. Sitt Gulsun fretted whenever the door to the parlor was opened, even for the purpose of cleaning the room. Her anxiety mounted when visitors came and sat on the chairs, sipping the drinks they were served. She kept her eyes fixed on a guest's hand clutching his glass of tea, shifting her gaze only to fasten it upon the guest's "silly" wife (as Sitt Gulsun refered to her after they had left). "My heart just about stopped every time she laughed. I said to myself, 'This night won't end well—the tea will be upset all over the needlepoint upholstery.' " And if guests came with their children, it was an actual crisis. Then would come a scowling visitor who never laughed, and who brought no children with her, and you would think she would be the ideal guest. But she would leave and Sitt Gulsun would say, "Her face was yellow as a lemon with envy. By God, I don't think we should admit any guests to the parlor—we should entertain them in the hall!" She would prepare incense, and pass the censer seven times over the needlepoint cushions and the three framed pieces. Then she would get a slip of paper, from which she would cut out the shape of a woman, pierce it several times with a pin, and then burn it, muttering prayers under her breath. Finally she would leave the room, carefully locking the door.

The locked door did not rouse Shagar's curiosity or any desire to cross the threshold. She knew what was behind the door: a set of gilded chairs crowded the room, so that only narrow passageways were left between the clunky furniture, passageways made still narrower by a table whose black marble surface Shagar could never look at without being reminded of the time she had bumped her head on its edge. The blood had poured from her head, resulting in a trip to the hospital and several stitches. After this the wound had healed, and all that remained of it was a fine scar beneath her right eyebrow, and the echo of a child's mockery—one of her schoolmates had laughed at the white bandages around her head. The three pieces in their frames and the upholstered cushions made her all the more eager to flee from the room. There was just one thing that she wished she could remove from it: a picture of her mother and father, their wedding portrait.

Her father was laughing; it seemed that he wanted—out of respect for the portrait—to restrain his joy and show himself a somber bridegroom. But laughter got the better of him, so that he appeared suspended between two states: the animation of a young man who has won the girl of his choice, and the ritual sobriety of a formal wedding and the portrait that fixes it in the eyes of the family for all of posterity. Her mother stood beside him in a long white gown whose splendor was incongruous with the childishness of her face—a face in which sweetness, innocence, and a little uneasiness could be discerned. She too was suspended, between girlhood and womanhood: the girl fearful and wondering, the woman accepting her own diffident role. Her father had been twenty-seven years old, her mother seven years his junior.

Shagar studies them now, years after their deaths. She is aware, now that she herself is past 50, that she is many years older than they. In the never-changing portrait, her parents are mere children, and she has become, with the passage of time, mother to her own parents.

What happened? Why did I leap so suddenly from Shagar the child to middle-aged Shagar? I reread what I have written, mull it over, stare at the lighted screen, and wonder whether I should continue the story of young Shagar, or return to her great grandmother, or trace the path of her descendants to arrive, once again, at the grandchild. And the ghosts—should I consign them to marginal obscurity, leaving them to hover on the periphery of the text, or admit them fully and elucidate some of their stories? And should I confine my narrative to the ghosts of the grandmother's acquaintance, or expand the subject to include succeeding generations of ghosts? And would anyone put up with such writing? Matters could come to a decision to erase what I've written, and begin instead by setting down my own story directly. And Shagar? Should I keep her and interweave our stories, or drop her and content myself with telling about Radwa? But then, why did Shagar come to me when I started out writing about myself? Who is Shagar?

I moved the cursor to the list of files and pressed, then moved it to "shut down," and the white screen was replaced by a black one. I turned off the machine and went to bed. My sleep was disturbed by dreams about which I remembered nothing but their oppressive presence. I woke up exhausted, as if at the end of a long day. As I sipped my coffee, I once again considered the problem of what to do about Shagar.

I turned on the computer and selected "Word," then opened the "Shagar" file. I wrote:

What's with you, Shagar? You conduct your life like a decrepit old mule. Would horses turn into mules? And this heavy, overflowing wagon— what did it look like at the beginning of its journey— a tub full of fragrant jasmine, or is it just that memory endows the past with what it never contained? In the morning, everything looks difficult. What are you afraid of? Has fear defeated you, or is it defeat that you're afraid of? Or are life and death stripping down shamelessly and having it off on your bed, while you watch, totally helpless, soundlessly screaming? You say these are all illusions, you'll get rid of them; you get up and go to the sink, get your toothbrush, and—Good Morning!—your coffee. The dust of battle hasn't settled yet, but you—as you drive your car across the overpass you are seduced by the details: a palm tree standing proud, a roaming cloud, the river's current; another driver rudely passes you, so you curse his father in a loud voice, only to discover that your voice doesn't reach him, because the car windows are all the way up.

(The warrior had died/ A man came and said, "Don't die, for I love you very much!"/ But the body— alas!—went on dying./

Two more came, and they said to him:/ "Don't leave us! Take courage! Return to life! / But the body—what sorrow!—went on dying./

Next came… (all of his loved ones)/ they surrounded him; the sad figure saw them, and emotion stirred him/ he rose slowly/ he embraced the first person; and he proceeded to walk.)

Shagar signed her name and the brown envelope that she had previously sealed and submitted to Control two weeks earlier was handed to her. She took the envelope and headed to the examination room. She looked at her watch: precisely seven minutes before nine. She waited two minutes. She handed the envelope to the supervisor, who slit it open.He gave a sheaf of examination papers to the proctors, who spread out rapidly among the rooms and corridors in order to distribute the papers to the students. At exactly nine o'clock, the test began.

From the time she had become obliged to walk with a cane, she had accepted her condition with a calm that surprised her. Had she become reconciled with the problem? What was the problem with a 50-year-old woman's having to walk with a cane because of her afflicted leg? She'd had plenty of time for running, so what harm was there in entering her sixth decade accompanied by a cane to remind her that the child and the girl, and the glory of the woman in her thirties and forties, were all behind her now and had left her to the business of getting on with her journey toward old age? She forgot about the cane, forgot it was there. But during the examination she remembered it. She deplored the way it thumped on the ground, annoying the students, disturbing their concentration, and not allowing her to approach them quietly in order to cast a quick glance over their answer booklets and secretly ascertain whether or not they were copying from cheat-sheets they had brought in with them. The cane had become a sort of alarm bell; the students raised their heads and looked around, or kept their heads down, whether from shyness or because they had something to hide. She annoyed those who were sitting there in peace and quiet, concentrating on their answers, and she alerted the young cheaters with her early warning system.

She no longer walked around during examinations. She entered the examination room and chose a spot that allowed her to observe the students: a military guardsman supervising the prison complex from the highest watchtower— she lacked only a rifle to brandish in the faces of the prisoners… God, what sort of role was this?

The test ended. The proctors collected the answer booklets. She went back to her office. She ordered some coffee. She sipped it. She signed some papers. She talked to a student about the topic of his research. She went down to Control to pick up the answer booklets. She counted the papers, and signed for them: 556 answer booklets for a fourth-year test on modern history. One of the interns had been responsible for tying them up with a length of twine. The office boy carried them to her car. At home, she placed them in her office, and locked the door. Tomorrow the annual ritual would begin.

In bed, she closed her eyes to sleep, but then she saw the papers she had corrected in the course of thirty years. Tens of thousands of answer booklets rose up around her like pillars, closing off all open space and leaving her a small, confined area in which to sit. In her hand was a red pen. Her glasses rested on the bridge of her nose. A booklet was open before her, lines of responses overflowing its pages. She opened her eyes. Alarmed, she raised herself to a sitting position. She sat cross-legged on the bed.

No, it's not so! There is always a window, some light, a bird in flight. Don't deny it, Shagar— and it was never just one bird. They always come to you, always surprise you, these unexpected birds that emerge from among the papers and carry you with them into open space.

Who's calling at this hour of the night? She picked up the receiver. "'A successful woman?' What's that got to do with me? 'The criteria of success?' Madam, it's the middle of the night!" She hung up, and disconnected the telephone.

Specters © 2011 Radwa Ashour, Translation © 2011 Barbara Romaine. First American

edition published 2011 by Interlink Books. 9781566568326. Reprinted with permission.