"I like change, you go first," the joke goes.

Those of us who have lived enough years to have some perspective on the past, have undoubtedly concluded that, short of a crisis or revolution, change does indeed occur at a snail's pace, if at all. And without constant pressure any progress can be arrested or even turned back for a time.

With this in mind, at the beginning of this new year, Belletrista staff have done some research into the place of women in our literary culture. Decades after a second women's movement swept the Western world, where do we stand now?

About a year ago, VIDA, an organization founded in 2009 to "explore critical and cultural perceptions of writing by women," published online "The Count," a study of the gender disparities in a large number of prominent literary venues in the US and UK for the year 2010. The results, visually presented in colorful pie charts, were disheartening. By publishing this, VIDA wanted to stimulate and shape the discussion—and clearly bring it to a wider audience. The most obvious and often asked question is why such a disparity exists in the 21st century. There are many answers, most of which have been well aired. A notable response to the VIDA survey and to the question of why, comes from Laura Miller on Salon.com. Miller pulls in the results of several other surveys to offer possible explanations and to give a broader perspective. Fewer women are being published, one intriguing report says. There is a gender gap in what people choose to read, says another equally intriguing survey.

To the continued discussion, we offer the results of an informal survey of the current gender disparity of major literary awards. Awards and nominations such as these not only raise the profile of a writer, sell books, and direct a great number of people's reading, but it gives the writer a more permanent place in the literary canon of the respective culture, and thus serves as a representative for it. Should not literature, but also literary awards, broadly represent the varied experiences of the people in the culture from which it is derived? And if it doesn't, what does that mean?

Our survey focuses on general fiction awards during the past twenty years. We live in a time where most Western women, if asked, assume gender parity, despite any evidence. Each year, it seems, a discussion arises about the continued necessity of the UK's Orange Prize; a prize open only to women, established in the early 1990s out of frustration and anger over the lack of women writers represented on the Man Booker Prize lists. Sadly, in the last twenty years, the Booker Prize has awarded to women even less than they did in the previous 20 years. However, there is no doubt that the Orange Prize has significantly raised the profile of many women writers from throughout the English-speaking world who are published in the UK; now, thanks to social media, they can boast an enthusiastic, international audience.

In Australia this year, the first Stella Prize, modeled after the Orange Prize, will be awarded. As in the UK, the Stella Prize was born of a similar frustration over the continued marginalization of women in Australian literary culture, and, in particular, the continued gender disparity in the Miles Franklin Award winners, an award with a dismal record of awarding to women (ironically, the award takes the name of Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin, an early 20th century Australian writer and feminist. This is also where the new Stella prize name originates), while often repeatedly giving the award to the same men. Although the necessity or value of a segregated approach to correcting gender disparity is often disputed, the disparity itself is not. One cannot assume that without action of some kind, disparities will correct themselves in what might be considered a reasonable amount of time.

Our report groups similar awards, and adds others for perspective. For our main focus, we have chosen juried awards, and also awards whose archives are readily available online (and in a language we can read). Awards mentioned, with links, will be listed at the end of the report. We should add here that we assiduously looked up names to determine the gender of unfamiliar authors; one certainly could not trust names such as Jean, Kim, Gill or Alex to be female ones; never mind Esi, Tove, Nanae, or Muthoni.

Although we chose mostly juried awards, we did not look at the gender makeup of those juries. Women, as certainly as men, can be unconscious preservers of the status quo.

We realize that such a small sampling of two decades, and the small number of winners within each decade, tells us little more than the current status, but even so the results are quite interesting. There are many more awards we would have liked to include, but it was necessary to limit the scope of our survey.

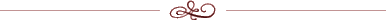

To begin with, the following chart shows the percentage of female to male winners in four major awards from four English-speaking regions: the UK, Canada, Australia, and the United States.

Here are the same four awards showing the percentage of women making the award's shortlist versus the percentage of women who actually win. We would have liked to compare longlist percentages also, but many awards did not post longlists or their listings are incomplete.

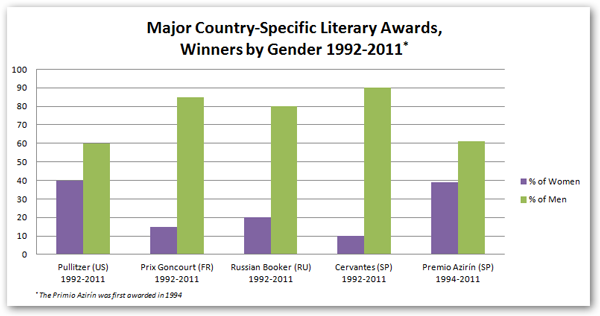

For perspective, we looked at several country-specific awards during the same twenty year period:

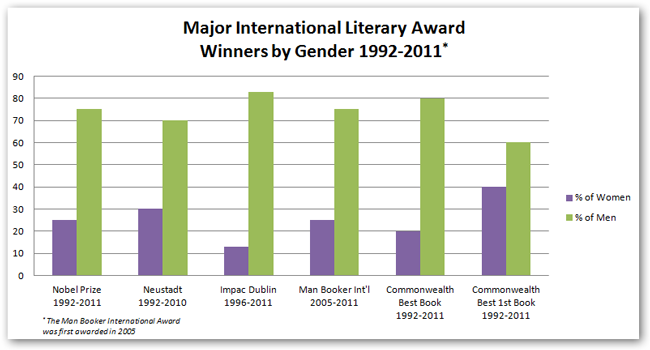

The fourth chart includes international prizes or those awards with a broader reach. The criteria for these awards vary, so one cannot compare them directly; nevertheless it is still worthwhile to look at where they stand on awarding to women.

One has to look back beyond the last twenty years to see the Nobel Prize results as encouraging. Of the 108 awards given, twelve have been awarded to women, but half of those awards were given in the last twenty years. The Impac Dublin Award, one of the richest literary awards in the world, has only awarded to two women in its sixteen-year history, and both of those happened now over a decade ago.

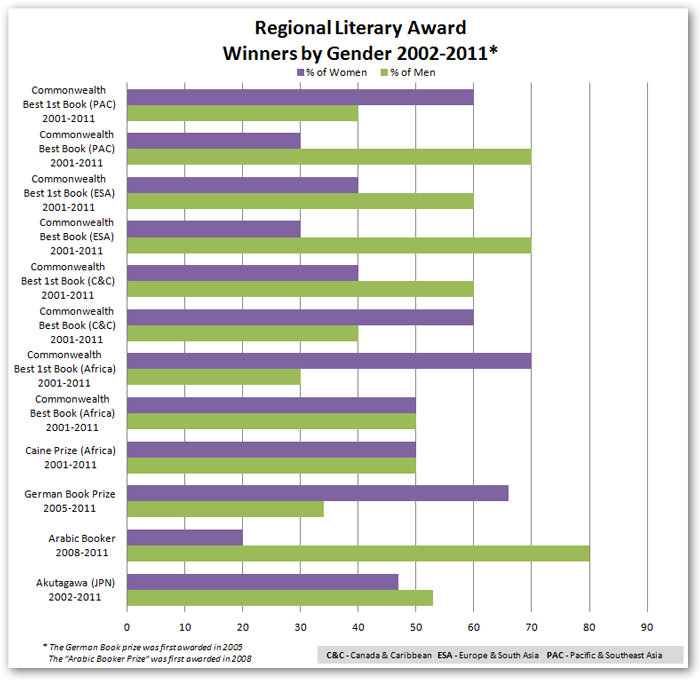

And finally, for added perspective, we look at a number of other awards over the last ten years. Note: Any ties are counted as two awards.

So what, if anything can be concluded from this survey? Decadal trends cannot be determined from a small sampling of only twenty years, but a clear disparity between women and men award-winners is constant over a range of global cultures during this period. Pointing this out, of course, doesn't imply that there is a widespread conspiracy or conscious effort to exclude women. These comparisons do, however, appear to confirm once again that old habits of thought, such as giving preference to literature written by men, change slowly.

Why should we care, you ask. Because it is about fairness, about equality, but it's also about widening our perspectives and reading and enjoying great books. We cannot correct the disparities of the past, with awareness we can change the future. Today, can serious readers—whether men or women—be considered well-read without including the work of contemporary women (and others different from themselves) in their reading? Defensive claims of gender-blindness are mostly just that, defense or justification; for, as is the case with issues of race, all of us have our "invisible backpacks" of unconscious biases, which quietly affect our choices. Only through awareness can we examine and then overcome our biases.

Change can begin, at the grassroots level, one reader at a time.

VIDA http://vidaweb.org/

VIDA's "The Count" http://vidaweb.org/the-count-2010#

"Literature's Gender Gap" by Laura Miller, Salon: February 9, 2011

Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin

"White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Backpack" by Peggy McIntosh

The Orange Prize for Fiction

The Stella Prize

The Nobel Prize in Literature

The International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

The National Book Award

Scotiabank Giller Prize

The Man Booker Award

The Miles Franklin Award

The Pulitzer Prize

The Prix Goncourt(French site); Wikipedia list of winners in English

The Russian Booker Prize, Wikipedia list of winners in English.

The Miguel de Cervantes Prize (Spanish site), Wikipedia list of winners in English

The Premio Azorín,(Spanish site) Wikipedia list of winners in English

The Neustadt International Prize for Literature

The Man Booker International Prize

The Commonwealth Prizes, Best Book, Best First Book, and the regional winners.

The Caine Prize

The German Book Prize (German site), Wikipedia list of winners in English.

The Akutagawa Prize, Wikipedia list of winners in English.

International Prize for Arabic Fiction "The Arabic Booker"