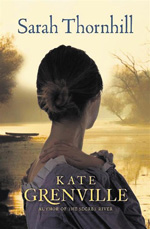

Sarah Thornhill is the sequel to Grenville's widely acclaimed novel The Secret River, which told the story of freed convict William Thornhill making a home on the Hawkesbury River in the newly settled colony of Australia. Now, several years later, Thornhill is a prosperous landowner and his youngest child, Sarah (the narrator), is just reaching womanhood. Grenville tells of the Thornhill family, ruled by a strong-willed stepmother, and of living the good life in the bush. Sarah describes the major events in her life—young love, heartbreak, births, deaths and marriages. Always pushing the narrative are questions to be answered and secrets to be revealed.

Grenville's trademark prose is understated and with Sarah Thornhill she goes further by writing in Sarah's vernacular. For example, Sarah habitually replaces the word "have": "If I could of walked on air I could of gone straight across to that stretch of dust and pebbles." This device lends a certain charm to the book and there are some wonderfully descriptive passages:

Sarah's life is not all sweet, however, and she is affected by the problems of the local Aboriginal people. Dispossession is referred to sparingly but is ever-present. Local Aborigines, once the landowners, now work for Mr Thornhill, or come begging at his door. Australia's Indigenous people, to this day, fight to have areas of their land returned.

Another topic which Grenville addresses, albeit obliquely, is the removal of Aboriginal children from their families, a practice which was in place during the 19th and 20th centuries. The idea was to take biracial children, teach them the white ways and thereby make them acceptable members of society. Shameful, yes, and only recently acknowledged by the Australian government. These children are referred to as The Stolen Generation and although there is no stolen Aboriginal child in Sarah Thornhill, Grenville finds a conduit for this tragic aspect of Aboriginal history. Intertwined with this is the archaic theory that Aboriginal people should better themselves, and do so by abandoning their traditional ways. These days the rights of Aboriginal people to maintain and celebrate their culture is mostly respected but prejudice remains. Likewise, Sarah Thornhill< highlights the hypocritical attitudes of some white Australians that still exist.

Grenville's novel is both historical and topical. It is an interesting blend of page-turning suspense, naive charm and

serious moral issues. The writing is lovely, and Sarah Thornhill is deserving of a wide readership.

Text Publishing (AU), paperback, 9781921758621

Grove Press (US), hardcover, 9780802120243 (June 2012)