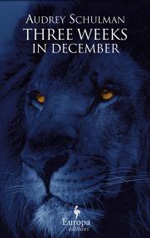

Advocacy fiction can be a tricky business: it's easy for passion to slip into sermon or harangue, obscuring the identity of the work as a story. When that happens, I would argue that it might as well be an essay rather than fiction. Audrey Schulman's latest novel, Three Weeks in December, tackles the genre of advocacy fiction twice, alternating chapters of two stories on the theme of Euro-American involvement with Africa. Happily for the reader, she stays on the safe side of the line between fiction and essay.

In the first story, Schulman fictionalizes the actual events of the Tsavo Maneaters, a pair of lions who killed as many as 135 workers from the construction crews of a British railroad project on the Tsavo River in Kenya in 1898. Schulman substitutes her character, Jeremy Turnkey, in the place of the real John Patterson, the lead engineer of the effort and the man who eventually managed to shoot the two predators. At home in England, Jeremy was always vaguely uncomfortable, largely due to homosexual inclinations that he wouldn't fully admit even to himself and which made him an object of unease or amusement in nineteenth century society. On the Tsavo, where there is only one other Westerner amidst thousands of imported coolies and hundreds of natives, the pressures of society largely disappear, leaving Jeremy to confront his feelings.

Set 101 years later is the story of Max Tombay, an ethnobotanist who has Asperger's Syndrome. She inhabits a world where she is assaulted by physical stimuli, and to alleviate this she eats bland, colorless food to minimize taste; wears gray clothes to avoid color; and, most importantly, eschews physical contact whenever she can. It's also a world where social stimuli have no meaning: she memorizes muscle patterns to understand facial expressions and performs limited social niceties simply by rote. Max is commissioned by a pharmaceutical company to find the origin of a vine sample containing huge natural levels of beta blockers. All she knows is that it grows in the upper reaches of the Rwandan mountains, the home of the vanishing mountain gorilla.

The two stories tie together in the last pages of the book in a simple, but largely irrelevant, manner; their real purpose is to serve as mirrors for each other. The stories contrast in the effects upon the two protagonists of escaping from a society in which they did not fit. Max finds contentment among creatures who minimize touch, who don't look at each other's faces, and who spend long hours in quiet, concentrated activity. Jeremy, however, weakens: he begins to obsess about his appetites and finds that he is unable to be effective in an environment where the rules that guide decision-making are quite different. The novel is an interesting deliberation upon whether society helps us or hurts us.

It is the similarities between the stories' themes, however, that draw the most attention. Both protagonists come to understand the dual nature of civilization's presence. Jeremy recognizes that colonialism brings medicine and education, but also exploitation and destruction of native culture. Max knows that drugs created from the vine can save countless lives but that human encroachment into the mountains will destroy the gorilla's habitat and eventually cause their extinction. As we follow the journey of each from enthusiasm to reluctance, it becomes fairly apparent where Schulman's sympathies lie…at least to some degree.

She walks a fairly fine line in Jeremy's story. Despite the inherent excitement of the lions, I found his character and personal struggle not completely absorbing and, so, less able to balance Shulman's discourse on cultural imperialism. Fortunately, despite occupying half the pages, Jeremy was not half of the book for me. He was, largely, a foil for Max.

Because, make no mistake about it, this is Max's story. Instead of a character who, when we first meet her,

might bode to be the less interesting, Schulman has given us someone richly rounded. Max reaches out of the

pages and pulls the reader into her world and her thoughts, and we return to each of her chapters with excitement.

As a result, the homilies Schulman wishes to deliver—though no less overt—balance and enrich a beautiful story.

Europa Editions, paperback, 9781609450649