This year, the Orange Prize for Fiction turns 15. Like many teenagers, it's been through some rocky patches,

caused scenes, aroused stormy emotions, and been dazzled (briefly) by celebrity. Yet it is undeniable that

for all the controversy, the "Orange revolution", as Robert McCrum dubbed it in 2009, has been largely

responsible for stimulating a "new generation of remarkable writers".

This year, the Orange Prize for Fiction turns 15. Like many teenagers, it's been through some rocky patches,

caused scenes, aroused stormy emotions, and been dazzled (briefly) by celebrity. Yet it is undeniable that

for all the controversy, the "Orange revolution", as Robert McCrum dubbed it in 2009, has been largely

responsible for stimulating a "new generation of remarkable writers".

The Prize did not have an easy birth. An all-male Booker Prize shortlist in 1991 was the initial catalyst for a meeting in January 1992. Around 40 men and women from across the publishing industry came together with "no agenda", according to Kate Mosse, the Prize's co-founder and honorary director. "It was genuinely to talk about whether it mattered or not," she says, "that there were no women on the list, and that nobody had noticed." Out of research conducted by that group came the decision to create a new literary prize with two main objectives: to celebrate the very best fiction written by women on an annual basis, and to do so on an international scale.

The group quickly secured funds from an anonymous donor, but finding a headline sponsor proved more difficult. First announced as the UNI Prize in 1994, the Prize's original sponsor, the Mitsubishi Pencil Company, withdrew just days before the planned launch, citing a "change in marketing strategy". It was January 1996 before the committee was able to relaunch the Prize, with mobile telecoms operator Orange now on board.

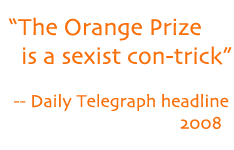

Mitsubishi's withdrawal has often been linked to hostile press coverage, characterised by some astoundingly

misogynist language. Reading the tirades published about the Prize, it's hard to believe it's actually

permissible to print much of it.

Making only women writers eligible for the Orange Prize has proved

impossible to swallow for many - despite the fact that, as Kate Mosse puts it, "all prizes have eligibility

criteria". It can hardly have helped that the sum of £30,000 on offer for the winner made the Orange Prize

by far the most lucrative on the British literary scene at the time, dwarfing the Booker's then £20,000.

Making only women writers eligible for the Orange Prize has proved

impossible to swallow for many - despite the fact that, as Kate Mosse puts it, "all prizes have eligibility

criteria". It can hardly have helped that the sum of £30,000 on offer for the winner made the Orange Prize

by far the most lucrative on the British literary scene at the time, dwarfing the Booker's then £20,000.

Media attitudes continue to be dominated by a focus on, as judge Lola Young put it in 1999, "friction rather

than fiction", underlining the importance of the Orange administrators' research programme. Kate Mosse explains,

"A lot of the research that has been done about the Orange Prize is about asking questions, not seeking

verification of our own already fiercely-held beliefs." One of its more infamous exercises was the 'shadow panel'

of male judges, undertaken in 2001. Given the same longlist of books, the men were given free rein to

select their own shortlist. "Their deliberations were very, very different," comments Mosse, "but they did

both choose the same winner. Which is incredibly wonderful, actually. You sort of feel a really great book

will out."

Media attitudes continue to be dominated by a focus on, as judge Lola Young put it in 1999, "friction rather

than fiction", underlining the importance of the Orange administrators' research programme. Kate Mosse explains,

"A lot of the research that has been done about the Orange Prize is about asking questions, not seeking

verification of our own already fiercely-held beliefs." One of its more infamous exercises was the 'shadow panel'

of male judges, undertaken in 2001. Given the same longlist of books, the men were given free rein to

select their own shortlist. "Their deliberations were very, very different," comments Mosse, "but they did

both choose the same winner. Which is incredibly wonderful, actually. You sort of feel a really great book

will out."

The shadow panel did highlight a persistent tendency to pre-judge books on the basis of their subject matter; shadow judge John Walsh's comment describing the 2001 list as "claustrophobic" was widely reported. Diana Evans, author of 26a, which won the inaugural Orange Prize for New Writing, is critical of a short-sighted obsession with topic. "The subjects that women choose to write about," she says, "are less important than the risks and leaps they take in style and form, the scope and reach of voice. It is indeed possible for a novel that deals with so-called 'women's issues' to be ambitious." Evans has a theory that the domestic is not considered by the literary establishment to be a valid topic for literary expression. "I think that male readers of subjective literature by women often immediately complain of claustrophobia because they are used to their own subjectivity being received as the language of wider society, as coming from beyond the 'domestic' realm and therefore holding more importance," she says. "They are too used to the sound of their own voice."

The shadow panel's deliberations did seem to support the idea that, as the psychologist sitting in on their discussions wrote, "men reading over the gender divide are now rarer." The Prize's 2002 survey of 4000 readers showed that men are extremely unlikely to choose books written by women with a female lead character—a tendency strongly linked to design and marketing, and especially to book jackets. "There is, if you like," says Mosse, "a generosity in female readers that they read men and women, and a lot of men read men." Sarah Churchwell, senior lecturer in American Literature and Culture at the University of East Anglia, and a judge for the Prize in 2009, has often observed this tendency amongst her students. "It's all identity politics. 'Women’s fiction is for women, black fiction is for blacks, gay fiction is for gays, ergo, because I am none of those things, I have permission not to read those things,'" she says. "I've said: do you read fiction only to reinforce your own experience? Do you not think that fiction can teach you something else about the wider world? ... They've been told that [women's] point of view doesn't matter; it's fine for us to have that point of view, but our perspective is not universal - their perspective is universal. It worries me a lot."

"For a great writer," continues Churchwell, "no subject is off-bounds ... It's such a limiting way of looking

at the world ... What does it say about our world that we think that the places that we live in are not worth

writing about?" Kate Mosse agrees: "Most people are lucky enough to have a home life - and that's men as well

as women. A brilliant novel set in the domestic is as important as a brilliant novel about war. And a poor novel

about either of those things will be claustrophobic, or bellicose." The Orange Prize offers a fantastic

opportunity for highlighting the best writing in this area - and for bringing those concerns properly into

literary discourse.

"For a great writer," continues Churchwell, "no subject is off-bounds ... It's such a limiting way of looking

at the world ... What does it say about our world that we think that the places that we live in are not worth

writing about?" Kate Mosse agrees: "Most people are lucky enough to have a home life - and that's men as well

as women. A brilliant novel set in the domestic is as important as a brilliant novel about war. And a poor novel

about either of those things will be claustrophobic, or bellicose." The Orange Prize offers a fantastic

opportunity for highlighting the best writing in this area - and for bringing those concerns properly into

literary discourse.

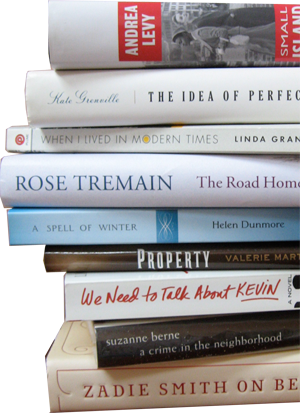

Even a cursory glance at the longlists and shortlists of recent years, however, demonstrates the falsity of the assumption that women writers focus predominantly on the domestic. The 2009 shortlist, for example, included Samantha Hunt's novel about the inventor Nikola Tesla, Ellen Feldman's exploration of the Scottsboro case, and Kamila Shamsie's epic Burnt Shadows that took in Hiroshima, Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay. Sarah Churchwell is rightly confident in the quality of the books selected by the 2009 judging panel. Discussing Marilynne Robinson's winning novel, she points out, "even a book called Home would be about politics, it would be about theology, it would be about philosophy, it would be about race, and it would be about a man." She notes that questions of multiculturalism and immigration surfaced in many of 2009's submissions, providing a real sense that the developing world was being written about in very interesting ways.

Kate Mosse also sees this increasingly wide-ranging choice of subject matter as a strong trend. "In recent years," she says, "[women writing about big subjects] has been happening more and more. Last year's winner, although it seems like a very delicate, beautiful, small book, is actually about what religion means - and obviously Andrea Levy['s Small Island] is about what it means to be British, and how we did let everybody that came over on the Windrush down - and of course, Chimamanda [Ngozi Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun] is a huge book about war."

Anxiety over gender politics obscures the Prize's grounding in solid advice from the book trade. 'All of us, but especially me, talked to a lot of booksellers, a lot of librarians, a lot of authors, a lot of publishers," Mosse recalls. "We asked the experts what they thought they wanted from a literary prize - where they felt some prizes worked better than others. We essentially asked the industry to give us guidance about how to do it - and pretty much, that advice was jolly good."

The Orange Prize's judges are given an open brief, and asked to look for "excellence, originality and accessibility". Kate Mosse elaborates: "It's not that all books will possess all three of these things - and it's a rare book that will possess all three - but a book that really tries to do something utterly different, even if it doesn't quite come off, is as valuable as a perfectly formed mini-Jane Austen." Sarah Churchwell praises in particular the advice that Mosse says she gives to the judging panel each year: "The point of this is to promote writing by women in English. The point of this is for it to be without borders. The point of this is not to have preconceptions about where value is going to come from."

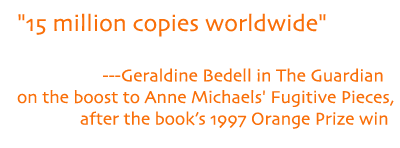

The openness at submission stage is matched by the openness in longlisting. The Orange Prize for Fiction was

the first major Prize to release a longlist - which it has done since its very first year, with important

implications for those authors whose books appear on it. "The longlist meant that there was room to highlight

a brilliant idea, or a fantastic writer," says Mosse. "We have an arrangement with libraries that they take

at least a thousand copies of each of the longlisted books, and the bookshops react to that, and we promote

the longlist. It means that books that have sometimes only sold a couple of hundred copies immediately

triple their sales - so it's dramatic compared to where they start."

The openness at submission stage is matched by the openness in longlisting. The Orange Prize for Fiction was

the first major Prize to release a longlist - which it has done since its very first year, with important

implications for those authors whose books appear on it. "The longlist meant that there was room to highlight

a brilliant idea, or a fantastic writer," says Mosse. "We have an arrangement with libraries that they take

at least a thousand copies of each of the longlisted books, and the bookshops react to that, and we promote

the longlist. It means that books that have sometimes only sold a couple of hundred copies immediately

triple their sales - so it's dramatic compared to where they start."

This very real impact on sales from both the main Orange Prize and the more recent Prize for New Writing is

clear evidence of the Prizes' success. "Winning the inaugural prize [for New Writing] worked wonders

(excuse the pun) for 26a," says Diana Evans, "particularly in combination with the attention it got

from other prizes. It increased sales dramatically and garnered translation deals, and my second book

[The Wonder] probably had a better chance with the bookshops as a result." Kate Mosse highlights

the impact of winning the 2007 Prize on Half of a Yellow Sun. "That book had already been on

Richard & Judy's Book Club," she points out, "but when [Adichie] won the Orange Prize, she sold in the

next couple of weeks 25,000 copies through Smiths - a high-street, mass-market retailer."

This very real impact on sales from both the main Orange Prize and the more recent Prize for New Writing is

clear evidence of the Prizes' success. "Winning the inaugural prize [for New Writing] worked wonders

(excuse the pun) for 26a," says Diana Evans, "particularly in combination with the attention it got

from other prizes. It increased sales dramatically and garnered translation deals, and my second book

[The Wonder] probably had a better chance with the bookshops as a result." Kate Mosse highlights

the impact of winning the 2007 Prize on Half of a Yellow Sun. "That book had already been on

Richard & Judy's Book Club," she points out, "but when [Adichie] won the Orange Prize, she sold in the

next couple of weeks 25,000 copies through Smiths - a high-street, mass-market retailer."

Adichie's mass-market success demonstrates another important aspect of the Prize: the high regard in which its selections are held by a huge breadth of readers. "That is what's so satisfying," says Mosse. "The Orange Prize has penetration with normal readers up and down the country and all over the world." Over its lifespan, the Prize has established a reputation for cover-blindness, picking out great books regardless of their marketing. This has given it a strong mandate to get books in front of readers that may initially appear daunting or 'difficult'. Sarah Churchwell stresses that this was a crucial consideration in 2009's deliberations: "We talked a lot on the judging panel about not making assumptions about what readers like... We just said, we're women, we think these are fabulous, let's put them out there and see what happens... We were confident that readers would like them if we put it in front of them."

2009's shadow panel of teenage judges was particularly successful in highlighting the more accessible books from the longlist. "They were more interested in story, and they were more interested in character," comments Sarah Churchwell, discussing the group's selections. "The youth panel did an excellent job of choosing out the rollicking, cracking good reads." The idea arose from a desire to incorporate the perspective of a lost generation of readers into the Prize. "Everyone knows that there's a black hole in fiction reading between when people leave school and when they start to have children in their 30s, particularly in the more literary fiction arena," says Kate Mosse. “People drop off from being regular bookbuyers in their 20s." Attempts to include a judge with more of a youth following ended when singer Lily Allen withdrew from the judging panel. The Prize decided instead to approach Penguin's teen reading website, Spinebreakers, to recruit younger readers. "It was just... the most exhilarating thing, to be involved with and to listen to those six people talking about the books," enthuses Mosse. "I went back to several books because of things that they said in that meeting; I suddenly thought... that's completely transformed that novel for me!"

The success of the Spinebreakers members' involvement with the Youth Panel, which is running again in 2010, also highlights the boost that the Orange Prize has received from the growth of online reading initiatives. The popular literary social networking site LibraryThing.com holds informal Orange readathons in January and July, and this year's chair of judges, Daisy Goodwin, has been updating her Twitter followers on her progress as she reads submissions before the longlist announcement in March. "A lot of people feel intimidated by bookshop events," says Kate Mosse, "but online everybody is equal; it just means that you can engage with a book, without feeling that anybody's going to go, well, that sounds foolish, or, what do you mean you've never heard of this person before? It can be an incredible community experience, but also utterly private."

The Youth Panel is the most recent initiative from a Prize that has continued to innovate. The success of the Orange Futures promotion (run in the Prize's fifth year to highlight new writers), combined with the UK Arts Council's interest in promoting short stories, led to recognition that there was room for a new prize. "We realised actually that if we combined the two, so the [New Writing] award...combined novels, novellas and short story collections, it would just be a boost to an area that's very hard to publish in," says Mosse. "It's very much about supporting women at the very beginning of their careers." Diana Evans concurs: "I have been on the judging panel for the [New Writing] award and was impressed at how fair, respectful and without cynicism the process was."

The continuing insistence on "excellence, originality and accessibility" is beginning to bear fruit for the

Orange Prize for Fiction. Not

only does it have real penetration with readers at all levels and across the

world, but its refusal to compromise on quality is also beginning to attract genuine recognition and

approval from literary society.

Sarah Churchwell points in particular to articles written during 2009

by Robert McCrum, former literary editor of the Observer, praising the Orange Prize for helping

to "transform the literary landscape", and singling out the 2009 shortlist for its literary excellence.

McCrum's comments are particularly significant given past criticism of the Prize for overvaluing the

accessible, and for promoting big-name authors regardless of the quality of the particular book submitted

for the Prize. "We genuinely chose a very strong list, that was intellectually robust," she says. "When

McCrum stands up and puts his weight behind it, and says, this Prize is a good thing, not just because it's doing

nice things for women but because it's recognising great literature, then I think we're starting to make headway."

Sarah Churchwell points in particular to articles written during 2009

by Robert McCrum, former literary editor of the Observer, praising the Orange Prize for helping

to "transform the literary landscape", and singling out the 2009 shortlist for its literary excellence.

McCrum's comments are particularly significant given past criticism of the Prize for overvaluing the

accessible, and for promoting big-name authors regardless of the quality of the particular book submitted

for the Prize. "We genuinely chose a very strong list, that was intellectually robust," she says. "When

McCrum stands up and puts his weight behind it, and says, this Prize is a good thing, not just because it's doing

nice things for women but because it's recognising great literature, then I think we're starting to make headway."

The sniping in the press is unlikely to go away. "The Orange Prize will always be an easy target," admits Mosse. "There will always be someone who for whatever reason does write a piece saying, you know, 'Down with the Orange Prize!' ...Most of these pieces never really engage with the Prize or what it has achieved ... You just have to weather that." Its persistence makes clear the Prize's importance: while it is still possible for people to get worked up about there being a prize 'just for women', there is still a need for it to exist. "There will never be an end to the vicious press, and I think it's healthy," says Diana Evans. "It provides a balancing factor. I think a woman who bashes a female initiative like the Orange Prize is a particular kind of 'feminist' (whether she calls herself that or not), the kind that wants to compete on an equal footing with men without appearing to receive any soft treatment."

Looking back over 15 years, gender issues have almost completely overshadowed the Prize's aims and achievements in supporting and promoting international writing. "We knew what we were trying to do was to say, 'there are some astounding books out there, and they're not all in the UK and America, you know!'" says Kate Mosse. "It was absolutely designed to celebrate international fiction by women." The widening of the field beyond Britain was an important factor: the Booker Prize's exclusion of writers from the USA was increasingly seen by the book trade as an old-fashioned anomaly. "It is significantly limiting of the Booker that it doesn't take all English writing - that it only includes Commonwealth countries," says Sarah Churchwell. "A lot of authors that appear to be American are not American," Kate Mosse points out. "They are Chinese women who live in America, or Russian women who live in America." The rather parochial and conservative British attitudes to publishing books from beyond the UK, however, still need to be properly addressed. "There is wonderful fiction out there that is neither British nor American," says Churchwell, "but we need to do better in terms of creating access."

The Prize has had significant impact for women writing further afield—something Mosse has witnessed firsthand on author tours to promote her own books. "It's had an enormous effect in Africa. The opportunities for women to be published have been certainly aided by the fact that their books are eligible for the Orange Prize," she says. "It's incredibly powerful in Australia and New Zealand; it’s seen as a career-changing prize to be shortlisted for." The Prize regularly receives requests from other countries for advice on setting up similar prizes. By February 2010, Mosse had been invited to eight different countries to advise on setting up prizes for fiction by women, and was due to visit Iceland during the month. "It is seen as a successful model," she says, "because in the end, it sells books. It's about promoting writing, and promoting reading."

And what about the future? Over the next 15 years, Mosse says she would personally love to see the Orange

Prize engaging with the question of literature in translation. "Only 3% of novels in this country are

translated fiction," she explains. "[Foreign publishers' lists] include translations from all over the

world. So I think British readers that only speak or read English ... are really badly served by the

rest of the world's literature. If there was any way in the next 15 years that the Orange Prize could

try and make a difference to that, getting more fiction translated, as part of an Orange Prize [offshoot]

... that would seem to me a really big contribution to writing and reading." Sarah Churchwell agrees: "We

should be reading more books that don't originate in English, definitely... an Orange Prize for translation,

I would be all for - I think that’s fantastic."

And what about the future? Over the next 15 years, Mosse says she would personally love to see the Orange

Prize engaging with the question of literature in translation. "Only 3% of novels in this country are

translated fiction," she explains. "[Foreign publishers' lists] include translations from all over the

world. So I think British readers that only speak or read English ... are really badly served by the

rest of the world's literature. If there was any way in the next 15 years that the Orange Prize could

try and make a difference to that, getting more fiction translated, as part of an Orange Prize [offshoot]

... that would seem to me a really big contribution to writing and reading." Sarah Churchwell agrees: "We

should be reading more books that don't originate in English, definitely... an Orange Prize for translation,

I would be all for - I think that’s fantastic."

So has the Orange Prize achieved maturity at the grand old age of 15? "It's only been treated with respect ... in the last, probably, five years," Sarah Churchwell notes. "To me [Robert McCrum's 2009 praise is] one of the first real accolades that it's gotten as not being the Booker's little sister, but as being a Prize in its own right." There has been an upturn in the percentage of women writers represented in other literary awards since the advent of Orange. Nonetheless, the increase should be larger: only 32 women have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize in the 15 years since 1996, compared to 31 in the 15 years preceding. "Telling me that equality has been achieved is not supported by the numbers," says Churchwell. "If you look at the Nobel, in 110 years there’ve been...11 [women writers] out of 110."

There is clearly scope to build on what the Prize has achieved so far. Yet it's not all about the numbers.

"The job of prizes is to celebrate the best within the criteria that any prize has set itself," concludes

Kate Mosse. "Keep your standards high, be passionate about promoting the books and the authors, and use

your publicity well ... to sell books, and to try and get a wider range of people engaging with literary

fiction." The Orange Prize has made huge contributions in raising awareness of great books, producing important

research into reading patterns (especially those influenced by gender), and promoting literature from

outside the Anglo-American corpus. "[The Orange Prize] has given women writers an advantage in that there

is more chance of their work getting noticed, a wider platform in an increasingly competitive market," says

Diana Evans. "Traditionally, writing by women was taken less seriously than that of male writers and I think

this attitude has taken a long time to filter out of the establishment, and indeed still exists in some corners.

Anything that attempts to redress this balance is both valid and relevant."

For more information on the Orange Prize for Fiction or the Orange Award for New Writers visit the Orange Prize website.

Rachael Beale has spent much of her career to date experimenting with combinations of words and technology,

either writing for technical companies, or doing technical things for literary ones. She graduated from the

University of Cambridge's Trinity College with an M.A. allegedly in "English Literature;" actual English

writers account for quite a small proportion of her reading, which tends to sprawl luxuriously across genre

boundaries. She makes time to read and talk about books by not doing things that normal people consider

essential (sleeping, cleaning, ironing...)