Maaza Mengiste and Nadifa Mohamed have most likely never met. Hence, they cannot be accused of a

conspiracy to firmly place their countries of birth on the map of the international literary scene

with their debut novels. Inadvertently, that is the case; Mengiste, an American-Ethiopian, writes

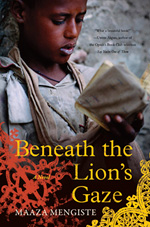

about the brutal Derg era of Ethiopia in Beneath The Lion's Gaze, while Mohamed, a British-Somalian,

writes about her father's journey through East Africa in search of his own father in Black Mamba Boy.

Though the two stories are very different, together, Mengiste and Mohamed have succeeded in telling

stories which add a richer depth and texture to the stories coming out of Africa in

recent times.

Maaza Mengiste and Nadifa Mohamed have most likely never met. Hence, they cannot be accused of a

conspiracy to firmly place their countries of birth on the map of the international literary scene

with their debut novels. Inadvertently, that is the case; Mengiste, an American-Ethiopian, writes

about the brutal Derg era of Ethiopia in Beneath The Lion's Gaze, while Mohamed, a British-Somalian,

writes about her father's journey through East Africa in search of his own father in Black Mamba Boy.

Though the two stories are very different, together, Mengiste and Mohamed have succeeded in telling

stories which add a richer depth and texture to the stories coming out of Africa in

recent times.

"Maaza Mengiste delivers an important story from a part of Africa too long silent in the World Republic of Letters": words used to describe Mengiste's, Beneath The Lion's Gaze by Chris Abani, the Nigerian author of Graceland and The Virgin Flames. Publishers Weekly goes on to say, "Mengiste is as adept at crafting emotionally delicate moments as she is deft at portraying the tense and grim historical material."

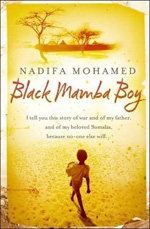

Equally as powerful and emotionally engaging is Nadifa Mohamed's debut, Black Mamba Boy, a

puzzling title but one that is symbolic of her father's unusual existence. Mohamed says Black Mamba

is the translation of her father's nickname because when he was born, he reminded his mother of a

black mamba* that had crawled over her stomach when she was pregnant with him.

Equally as powerful and emotionally engaging is Nadifa Mohamed's debut, Black Mamba Boy, a

puzzling title but one that is symbolic of her father's unusual existence. Mohamed says Black Mamba

is the translation of her father's nickname because when he was born, he reminded his mother of a

black mamba* that had crawled over her stomach when she was pregnant with him.

Beneath The Lion's Gaze is an exceptionally accomplished debut novel which evokes colossal emotions about the Ethiopian revolution of 1974 through Dr Hailu and his family. We relive the troubled days with Hailu, his dying wife and two sons, daughter-in-law and grand-daughter, their friends and neighbours as they struggle to survive their personal challenges and live through the chaos in the country. Poetically written with vivid descriptions, Mengiste says the inspiration for her book stems from "Memories of living in Ethiopia during the start of the revolution, and hearing the stories of my family and friends about their own struggles during that time."

Black Mamba Boy is both a historical document and a work of fiction. Mohamed takes us back

to Somalia in the 1930s, as she tells the jaw-dropping story of her father's life and journey.

It is the story of young Jama Mohamed and his childhood journey across East Africa after the

death of his mother, in search of his father - a man he has only heard of but has never met. It is

a journey of self-discovery, survival, exile, dislocation, dispossession and migration that will

take him through Somaliland, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Palestine and, finally, Wales. Mohamed

says the inspiration behind the book was simply to tell her 'father's story and about his generation

of Somalis.' And so she writes, "I am my father's griot, this is a hymn to him. I am telling you this

story so that I can turn my father's blood and bones, and whatever magic his mother sewed under his

skin, into history...I tell you this story because no-one else will."

Black Mamba Boy is both a historical document and a work of fiction. Mohamed takes us back

to Somalia in the 1930s, as she tells the jaw-dropping story of her father's life and journey.

It is the story of young Jama Mohamed and his childhood journey across East Africa after the

death of his mother, in search of his father - a man he has only heard of but has never met. It is

a journey of self-discovery, survival, exile, dislocation, dispossession and migration that will

take him through Somaliland, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Palestine and, finally, Wales. Mohamed

says the inspiration behind the book was simply to tell her 'father's story and about his generation

of Somalis.' And so she writes, "I am my father's griot, this is a hymn to him. I am telling you this

story so that I can turn my father's blood and bones, and whatever magic his mother sewed under his

skin, into history...I tell you this story because no-one else will."

Together both novels are of epic proportion as they chart a course in history of two African nations that may not be as prominent in fiction as other African countries, like Nigeria or Kenya. Both books have been in the making for five years. Mengiste is an MFA graduate from New York University, while Mohamed is a graduate of Oxford University, where she studied Politics and History.

Both novels are characterised by the extensive research conducted by both authors. Mengiste says her

research involved reading books, articles and journals, and talking to people and asking questions about

that particular period of time. She also travelled to Ethiopia. She further explains that while she

does not know the exact length of time her research took, "I reached a point in the novel where I needed

to begin connecting my characters and their plotlines to historical events." It was also important to

strike a balance between the historical aspects and the stories of the individuals she was telling.

"I feel that many times while writing this book, I was in negotiations with

history. At times, I had to make a conscious decision between historical fact and creating a

fictional truth of veracity that could convey more about the human tragedy of the revolution than

a simple data could." However, she asserts there were times when the story demanded historical facts

for the simple reason that people "Needed to know that a specific event had occurred to realise the

enormity of the trauma suffered."

Both novels are characterised by the extensive research conducted by both authors. Mengiste says her

research involved reading books, articles and journals, and talking to people and asking questions about

that particular period of time. She also travelled to Ethiopia. She further explains that while she

does not know the exact length of time her research took, "I reached a point in the novel where I needed

to begin connecting my characters and their plotlines to historical events." It was also important to

strike a balance between the historical aspects and the stories of the individuals she was telling.

"I feel that many times while writing this book, I was in negotiations with

history. At times, I had to make a conscious decision between historical fact and creating a

fictional truth of veracity that could convey more about the human tragedy of the revolution than

a simple data could." However, she asserts there were times when the story demanded historical facts

for the simple reason that people "Needed to know that a specific event had occurred to realise the

enormity of the trauma suffered."

Mohamed's research took her on a journey. She started by recording her discussions with her father, which led her to travel to Somalia, Djibouti and Eritrea to retrace his steps. She said, "My research spanned five centuries of Somali history, from the jihad against the Ethiopian Empire to the terrible war in the late 1980s. I went as far back as sixteenth-century texts. Most of the historical sources I used were from 1850-1945 when Europeans began to write about the region, and although they described the environment very well, they were pretty useless at describing Somalis as real people. Somali life has changed so drastically that some details have been lost as generations have disappeared, taking that knowledge with them, hopefully we can record more now."

Family, relationships among friends, relationships between the powerless and powerful of society,

poverty, violence, class, political and social divides, war, migration, dislocation and dispossession,

survival, and exile are some of the many themes explored by both authors. Mohamed says the theme of

migration is one she wanted to explore because "I'm an immigrant but I didn't know I was a third

generation immigrant. My grandparents and father had also settled outside Somalia and in similar

ways had to acclimatise to different cultures. Migration is still a huge issue for Somalis, we gain

and lose through it, and it was incredible to learn that from the mid-eighteenth-century, Somalis

have been smuggling themselves into countries that they know next to nothing about."

Family, relationships among friends, relationships between the powerless and powerful of society,

poverty, violence, class, political and social divides, war, migration, dislocation and dispossession,

survival, and exile are some of the many themes explored by both authors. Mohamed says the theme of

migration is one she wanted to explore because "I'm an immigrant but I didn't know I was a third

generation immigrant. My grandparents and father had also settled outside Somalia and in similar

ways had to acclimatise to different cultures. Migration is still a huge issue for Somalis, we gain

and lose through it, and it was incredible to learn that from the mid-eighteenth-century, Somalis

have been smuggling themselves into countries that they know next to nothing about."

Mengiste and Mohamed write with generous compassion for humanity which comes through in their characters, who have a varying depth of emotional facets. According to Mohamed, "With novels, you breathe life into a character, you make them whole and the reader can sink into their skin. We all feel grief, love, loneliness and every other emotion we can identify with in characters when we see them struggling with these feelings."

Through the character, one experiences the relationship between the powerful and powerless in society

and how that affects lives. Mengiste and Mohamed are adamant it was not about questioning these

vices in the societies they have written about, but about the world at large. Mengiste said, "I wanted

to examine the nature of power, the nature of resistance and try to understand what makes people do the

things they do. And it is not a matter of this mindset being an Ethiopian phenomenon. I think we just

have to look at the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the deep religious fears we have around the world,

to see that the relationship between the powerful and powerless is an ongoing point of conflict."

Through the character, one experiences the relationship between the powerful and powerless in society

and how that affects lives. Mengiste and Mohamed are adamant it was not about questioning these

vices in the societies they have written about, but about the world at large. Mengiste said, "I wanted

to examine the nature of power, the nature of resistance and try to understand what makes people do the

things they do. And it is not a matter of this mindset being an Ethiopian phenomenon. I think we just

have to look at the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the deep religious fears we have around the world,

to see that the relationship between the powerful and powerless is an ongoing point of conflict."

The stories both authors write about, they believe they needed to tell. Mengiste explains that by revisiting this period in the history of Ethiopia as a nation, she was compelled to tell a story that was indeed her own personal story. She said, "I wanted to tell this story because it was in part, the story of my family and my own story. The revolution was the reason so many Ethiopians fled and settled in other countries; it is the story of the Diaspora. I felt very close to this moment in Ethiopian history. I was compelled to tell this story because I wanted people to understand that there was a historical and socio-political context to this violence, it didn't just suddenly spring up. No group of people, Ethiopian or otherwise, are born violent or naturally predisposed to it."

Hence, she says her aim was to reveal the human cost of the national tragedy that occurred, to humanise the victims of the violence, and to show their dignity and fallibility. "We talk about violence in Africa as if it's a spectacle to be observed from a distance and shrugged off because Africans are prone to violence. I wanted to break that stereotype and show people resisting that violence."

For Mohamed, whose primary goal was to tell her father's story, she also wanted to bring across that, as

Somalis, "We have an interesting, largely unknown history that spans vast distances and that all of

the horrors of the last century are an important part of our story but are not the beginning or end of it."

For Mohamed, whose primary goal was to tell her father's story, she also wanted to bring across that, as

Somalis, "We have an interesting, largely unknown history that spans vast distances and that all of

the horrors of the last century are an important part of our story but are not the beginning or end of it."

And so, they both hope their books stir up discussions that would make people talk openly about this period of Africa's history. "I'd like people to ask what has become of those who suffered, and I want them to ask what has been done about those who perpetuated this violence. Where is Mengistu Haile Mariam, the head of the military junta and why is he still free?" asks Mengiste. Mohamed says while she had a lot she wanted her book to evoke, the foremost thing was the issue of "Identity and how it is formed when you are not rooted to a particular place of family or family unit. The problems that arise when young people are left to look after themselves and how patterns of abuse continue unresolved in communities."

Interestingly, both women say they hope the stories they have told in their novels evoke empathy, respect and wonder about how people survived. Mengiste sums up this point when she says, "I hope I've evoked a level of compassion about that period and in a broader sense, gratitude for the strength of the community and family."

Together, Black Mamba Boy and Beneath The Lion's Gaze reiterate the fact that no one incident,

occurrence or event in our lives happens in isolation. Different people and situations cross paths,

and they force us to make decisions and choose paths we may not have envisioned.

*the black mamba is the largest venomous snake in Africa

Belinda Otas (www.belindaotas.com)is a London-based journalist, writer and blogger.

She is interested in Africa, and is passionate about theatre. In fact, she is a theatre fanatic, and reads a lot of

novels and short stories by writers of African descent, but sprinkles it with her love of novels and works by authors

from different parts of the world. She believes that is what gives you the opportunity to experience other places and

cultures.

Belinda Otas (www.belindaotas.com)is a London-based journalist, writer and blogger.

She is interested in Africa, and is passionate about theatre. In fact, she is a theatre fanatic, and reads a lot of

novels and short stories by writers of African descent, but sprinkles it with her love of novels and works by authors

from different parts of the world. She believes that is what gives you the opportunity to experience other places and

cultures.

As a journalist, she has contributed to the BBC Online, BBC Focus on Africa, New African Woman and

Arise magazines, the UK Guardian newspaper, Global Comment, and Arab Comment, among others, and she has worked

at the BBC World Service as a researcher and broadcast journalist. Belinda

is working on her first stage play and so, will start calling herself a playwright when it is completed.

She reads a lot of poetry and writes poetry too.