For Caroline, as I recall growing up on a street bearing your name, this crossing now—to London —Tess

For Caroline, as I recall growing up on a street bearing your name, this crossing now—to London —Tess

This is what Tess Gallagher wrote in my copy of her book of poems Moon Crossing Bridge when I met her after a reading in 1992. Even here she is mythologizing a meeting, and this is the gift I most recognise her for. Almost all of her work has one kind of mythologizing or another to it: attaching acts to archetypal myths, mythologizing the ordinary, or self-mythologizing her characters or herself. It is evident in her work as poet, as short story writer, as carrier of a literary flame (of her husband Raymond Carver) and as essayist and memoirist.

At its heart her writing attempts to solidify the transitory, give breath after death to the fleeting and the ordinary. In fact little is ordinary through her eyes; she finds the core of her subjects, whether filled with feather or iron, and sings it into the hearts and minds and memories of her readers.

Born into a logging family in Port Angeles, Washington, where her mother worked alongside the men, Tess didn't realise for years how unusual this was. Her sense of womanhood was formed by this and by the violent outbursts the logging life led her father to, a life of bruising work and hard drinking. In her volume of essays Concert of Tenses, she tells us she is sixteen when she last feels the bite of the strap that her father beats her with, and how he realises that this is the last time that he will be able to punish her this way.

Later she records the murder of her uncle—the more accessible father figure in her life—at the hands of

three men, the murderer getting off scot-free whilst his accomplices are sentenced to manslaughter.

Yet in her short stories especially, there is rarely a sense of unfairness about the lives she records. The men and women she writes about are not so much sanguine as accepting. ‘This is my life' they appear to say. And this is Gallagher's craft, to give us these lives without judgement. She pays attention. She listens to her characters' voices. She doesn't compromise their stories. There is edge, there is humour and sometimes there is charm.

From the title story of her book The Lover of Horses, I can't shake the image of the story's great-grandfather, a man who ran off with the circus to follow a horse, returning home seven years later with nothing but the blanket and the headdress of the horse who had stolen him away. On drunken nights he could be found out in the field wrapped in the blanket with the headdress on his head, dancing as the horse had once done. Horses whinny and neigh in a number of stories and poems throughout Gallagher's oeuvre, but in this instance you find yourself hoping this story is true.

Another story in this volume, "Turpentine", tells of a woman who assimilates the stories of her new Avon lady, passing them on to others as her own. By doing so, she draws colour from the life of another to mythologize herself in her own eyes and subsequently in the eyes of others.

My amuse-bouche above barely do justice to the breadth and detail Gallagher can cover in a twelve page story; her stories are at times almost epic, if quietly so, and are never vertiginous. The stories never overbalance. They don't tilt unless she intends that they should tilt, and then it is from substance rather than volume. An inveterate storyteller, Tess Gallagher weaves stories within stories; stories become snagged like rags on a branch to other tales, or become tightly tethered to them.

In "The Red Ensign", from the story collection At the Owl Woman Saloon, the narrator sits in a hair salon called the Owl Woman Salon and wonders if Frank, a grey-haired man in late middle-age, has wandered in because he has misread the sign as "Saloon". She is initially resentful of Frank for his intrusion into what had once been a female domain, and she becomes even more exasperated when another man, clearly a buddy of Frank's, also arrives and settles in to have his hair washed. Sandwiched between the two men and subjected to Frank's conversation, she can't imagine he will have anything of interest to say to her, and can never imagine herself "tying her boat to his". However by the time he has had his hair cut, she has become intrigued by the knowledge that the two men, along with 5 others, provide the 21 gun salute for military funerals. He is about to walk out of her life, just as she might be considering tethering her boat to his. It is a tale of an ordinary circumstance with an updraft.

More than a short story writer, Gallagher began, and is better known, as a poet. The commonality between what she

writes as prose or as poetry is still that of mythologizing, and the layers of time and space. The stories appear

almost always complete. You may be tempted to imagine what might happen next, but they are whole in and of themselves.

Many of the poems, however, are like open windows. The reader can blow in and out of them. They often present or

cut open an idea and leave it to exist or be interpreted, to be found, formed or even misunderstood. Her poems can

be blunt or ambiguous, biographical, surreal or occasionally almost fairytale in quality.

Gallagher has said that her poetry has more biographical elements than her fiction, though often there is an abutment of incidents from different times and places that leads to a fictionalisation. Her poems speak of the personal and the universal in one breath. They are the memory of breath and the breath of memory.

In several poems in the volume Amplitude, the narrator returns to the memory of those who have died, bringing them into her future, revisiting their pasts.

When your widow had left the graveside

and you were most alone

I went to you in that future

you can't remember yet [...]

In this poem the narrator appears to be asking for release from the departed, asking him to wash away the history they have together. As she was not his wife, then she must have played some secret part in his life. She whispers instructions to his ghost, requesting him to cleanse her from head to toe, reliving memories and letting them wash from her soul. In the end she acknowledges their shared joy in the past, and walks forward to her tomorrow without him.

Let me go freely now.

One life I have lived for you. This one

is mine.

— from "The Ritual of Memories"

In her poetry especially, Gallagher is often in conversation with the dead, talking to them. She also uses narrations of one side of a conversation with a silent other. These often take place in restaurants and cafés, as in "The Dogs in Bucharest" and "Dream Doughnuts" from the volume Dear Ghost,. She is alert to the pellucid state of mind that can be achieved in personal conversations or thoughts that occur in public places, as if one is encapsulated by some invisible boundaries that permit deeper feelings to rise to the surface. Her narrators may be surrounded by others, and even if they are not always unheard by those at tables nearby (and the reader), they are still protected, still almost incognito.

Gallagher's poems allow the reader to attain an intimacy with the poet. Irrespective of whether the stories within them are biographical or imagined, it is possible to touch the inner spirit of their creator.

It would be impossible to write about Tess Gallagher without acknowledging her eternal connection to the life and creativity of her husband Raymond Carver. Carver died in 1988 at the age of 50, and she has been the keeper of the flame with regard to his memory and his work. She has been involved with the filming of his short stories, and in her own poems and essays she has shared moments of their life together. In Soul Barnacles: Ten More Years With Ray she has gathered together fragments of memoir, diary, photos and essays that speak of their lives and of their creativity.

One of Tess Gallagher's most recent projects has been to set down stories told to her by Josie Gray, a seanachi (traditional Irish storyteller), into the written word. These appear in their book Barnacle Soup: And Other Stories From the West of Ireland.

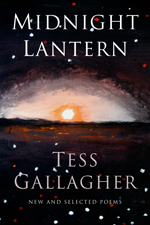

Gallagher's most recent collection of selected short stories is The Man from Kinvara and her new collection of poetry, Midnight Lantern: New and Selected Poems, is forthcoming from Graywolf Press in October.

In the poem "My unopened life" from Dear Ghost, Gallagher describes exactly how I feel about her writing:

The bowl of the spoon

collects entire rooms just lying there next

to the knife.

She waits and records. She pays attention. There is a seamlessness and an ease to her art and yet she is undoubtedly

a craftswoman. Or, like her mother, she is a woman logger, logging in words.

Caroline McElwee is a daydreamer, occasional writer, book addict: buying, caressing, smelling, reading, reading, reading; and she is a

lucky member of the London Library—heaven on earth! She lives in London.