There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried To Kill Her Neighbor's Baby: Scary Fairy Stories, selected and translated

from the Russian by Keith Gessen and Anna Summers (Penguin, 2009)

Immortal Love, translated from the Russian by Sally Laird (Pantheon Books, 1995)

The Time: Night, translated from the Russian by Sally Laird (Vintage, 1995)

In Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's fiction, there is no escaping the dangers

of Russian life as lived in the late Soviet, and then the post-Soviet, period: no escape in reality, and no escape in

fantasy—or, if fantasy permits some escape, then it is only temporary. You can flee into the forest, but danger

will follow you there. The only consolation is that there is a whole lot more forest left to flee into.

Two of the main dangers confronting the women in Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's fiction are men, and other women. Homo Sovieticus, and for the matter Homo post-Sovieticus, does not come across well in her fiction. He's drunk, feckless, faithless, and quite often jobless. If he does have a job, he runs nameless Institutes for his own benefit and that of his cronies, maintaining mistresses in a depressing absence of style, or comes back from the horrors of Army service or of prison never quite the same. Whatever you do, don't let him get you pregnant.

There is some refuge to be had in female solidarity, but it is limited and unreliable, likely to turn on you, to steal your man (whether or not he's worth stealing) and make off with your Moscow apartment. (Mind you, everyone wants to make off with your Moscow apartment.)

Every so often, the hand of a decaying State reaches into your life and rearranges it in arbitrary ways, taking your mother and her dementia away to a psychiatric hospital, inflicting the aforementioned Army and prison system on your male relatives, paying or failing to pay your pension.

Above all, like Poe's Red Death, stands vodka, the boon companion of a convivial Friday night, but also the maker of broken homes, the proximate cause of ugly fights and ugly lives.

Still, mustn't grumble! That would have been the reaction of World War Two-era Britons to this litany of woes, and to a substantial degree it's the reaction of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's protagonists as well—especially those in the collection entitled, with rich irony, Immortal Love. These are women on the lower reaches of the professional and intelligentsia ladders—translators, bureaucrats, junior members of the aforementioned Institutes—so they are by no means the lowest of the low, and for the most part they have those coveted Moscow residence permits, but their expectations in and of life are severely limited. Love, in Immortal Love, is never immortal, rarely long-lasting, often furtive, and generally with someone else's fiancé or husband.

People are stuck in social as well as economic ruts, and though Irina A may break up with Dmitri B and run off with Natasha C's husband, it's likely they'll all gather around the same table again before long, with a few awkward glances exchanged early in the evening, some sarcastic remarks later, and the odd punch thrown when everyone has reached the sliding-down-the-wall stage. The most that can be hoped for from life, it seems, is a few fond memories to carry off into the night, a single youthful encounter, a passionate glance preserved in memory.

And children, what are they good for? You love them passionately when they are little, cater to their every whim, and they repay you with indifference, resentment, and treachery. Such, at least in her own estimation, is the lot of Anna Adrianovna, the protagonist, narrator, and dominating voice in Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's short novel The Time: Night.

Anna Adrianovna is a poet, and throughout the novel she compares herself with her idol, another, more famous Russian poet named Anna. Now, Anna Akhmatova's own life was not without its difficulties, but who can deny that they pale into insignificance compared to the troubles visited upon Anna Adrianovna? Barely earning enough to live on, our protagonist copes with her deadbeat children, all of whom take everything she offers, a good proportion of what she isn't ready to offer, and give back nothing but scorn and resentment in return. Only Tima, darling Tima, her adored grandson, doesn't push her away, though he is forever hungry. He accompanies Anna Adrianovna on her missions to scrounge food and money from acquaintances until the arrival of her next pension cheque, or some pittance of a payment for her poetry. And when she finally does lay her hands on some food or money, those ungrateful wretches, her children, eat or drink or take it all.

What saves Anna Adrianovna from being a Russian Little Dorrit with worse skin and fewer prospects, a figure entirely

of pathos whom one might get tired of long before the end of even a short novel, is that she is as much a comic creation

as a tragic one. The reader can see, as Anna Adrianovna cannot, what a monstrous egotist she is, and how her family

are desperate to escape from her suffocating attempts to control every aspect of their lives. Whether it's coming up

with sardonic annotations for her daughter's secret diary, or shooing away the gangsters coming after her son, her

attitude to her family swings between concern and contempt. She's a wonderful, passionate, infuriating creation, and

The Time: Night is a tragicomic apocalypse of the first order.

The stories in Immortal Love are told in a low-key, Chekhovian register. The narrative of The Time: Night has the madcap energy of despair. The tone, and the genre, of There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried To Kill Her Neighbours' Baby is different again. The subtitle brands these as "Scary Fairy Stories", but these stories range over fantasy, folk-tale, and dystopian materials. These stories stake out similar territory to such other contemporary Russian writers as Ekaterina Sedia and Viktor Pelevin, but – and this is the fixed point in Petrushevskaya's fiction, or at least, in these three books—the focus is firmly on what happens to women and their families, not on what happens to the outside world.

The dystopian strain in twentieth century Russian literature is strong. So was the utopian strain in much of the fiction and poetry written in the post-Revolutionary period, but that utopianism became codified, and discredited, in the false pieties of socialist realism. Yet Petrushevskaya's dystopias are barely distinguishable from the reality of a collapsing state.

"The New Robinson Crusoes" tracks a family's attempts to survive an unspecified social breakdown. Their strategy is to escape further into the woods each time discovery threatens, and the teenage narrator regards each retreat, each cunning stratagem to evade thieves and mobs, as a minor triumph: yet with each, the family is thrown more completely on its own resources. They have a rifle, and a cat to hunt mice, and a dog to hunt rabbits. They have skis. They are already preparing their next refuge.

"The New Robinson Crusoes" is subtitled "A Chronicle of the End of the Twentieth Century". It first appeared in Novy Mir in 1989, but it could just as well have written about life on the outskirts of Detroit in 2008.

"Hygiene" runs along similar lines, though the driving force this time is plague rather than social breakdown. In many of these "scary fairy stories", the antagonist is Death; the stories revolve around the lengths to which people will go to cheat Death, and the various prices they have to pay to do so.

The good news is that the protagonists often come out on top—much more so than in the realist stories collected in Immortal Love. Sometimes, as in "The Black Coat", Death has to settle for second place. In others, we can at least declare the contest with Death a no-score draw.

Of the three books I've looked at in this article, There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried To Kill Her Neighbours' Baby is my favourite. Despite its comic efflorescences, The Time: Night is a desperately sad book about loss, about personal and social failure; but even it is light-hearted by the standards of Immortal Love with its story after story about love's limitations. There Once Lived… has a greater range of feeling and affect, from the pitch dark to the surprisingly light-hearted: "Marilena's Secret", the tale of two women's escape from the spell of a cruel magician, had me laughing out loud by the end.

Great Russian writers aren't known, on the whole, for writing the feel-good hits of the summer, and Ludmilla Petrushevskaya is, in my judgement, a great Russian writer. Her fiction in whatever mode she chooses to employ— comic, horrific, surreal, realistic—is held together by a precisely deployed technique and the careful selection of what to tell and what to imply.

It's dangerous outside, in the wilds of post-Soviet Russia. For that matter, it's dangerous inside too. You will need a guide through these dangerous zones, and Ludmilla Petrushevskaya is admirably equipped for the task.

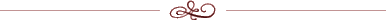

"Ludmilla Petrushevskaya was born in Moscow in 1938 and is the only indisputable canonical writer currently

writing in Russian today. She is the author of more than fifteen collections of prose, among them the short novel

The Time: Night, shortlisted for the Russian Booker Prize in 1992, and Svoi Krug, a modern classic

about the 1980’s Soviet intelligentsia. Petrushevskaya is equally important as a playwright: since the 1980s her

numerous plays have been staged by the best Russian theater companies. In 2002, Petrushevskaya received Russia’s

most prestigious prize, The Triumph, for lifetime achievement. She lives in Moscow." Her latest book, not yet

translated, is Stories from My Life, an autobiographical novel, pictured here.

Tim Jones is an author, poet, editor and anthologist

who lives in Wellington, New Zealand. His third collection of poetry, Men Briefly Explained, has recently been published.

As a reader, he especially enjoys Russian and South American literature in translation, poetry from

New Zealand and around the world, and science fiction—plus everything from Elizabeth Jane Howard novels

to Buffy comics.