Even literary critic, writer and philosopher Hélène Cixous, one of Clarice Lispector's

keenest readers, is ambiguous in her assessment of Lispector: "Imagine", she says, "if Kafka had

been a woman. If Rilke had been a Jewish Brazilian born in the Ukraine. If Rimbaud had been a

mother, if he had reached the age of fifty. If Heidegger had been able to stop being German".

What you get is something approaching Clarice Lispector.

Even literary critic, writer and philosopher Hélène Cixous, one of Clarice Lispector's

keenest readers, is ambiguous in her assessment of Lispector: "Imagine", she says, "if Kafka had

been a woman. If Rilke had been a Jewish Brazilian born in the Ukraine. If Rimbaud had been a

mother, if he had reached the age of fifty. If Heidegger had been able to stop being German".

What you get is something approaching Clarice Lispector.

Chaya Pinkhasovna Lispector was born on 10 December 1920, the third daughter in a family of Russian Jews who were fleeing the pogroms. They found themselves in Western Ukraine at the time of Chaya's birth and subsequently escaped into Romania, where they were granted visas to Brazil thanks to a family connection. On arrival in Brazil they settled in Maceió, a small city in the northeast; the family adopted Brazilian-sounding names, and one-year-old Chaya became Clarice. European roots notwithstanding, the adult Clarice identified herself resolutely with Brazil: "Obviously I am Brazilian, and don't allow anyone to think otherwise".

The Lispectors' early years in Brazil were tough, with mother Marieta suffering from increasingly serious health problems and father Pedro struggling to support his young family. The family moved to the larger city of Recife in search of a better life, but Marieta's health continued to worsen and she died in 1930, when Clarice was nine. None of this kept Clarice from showing early academic promise, or from announcing a precocious desire to write.

Her father continued to find life hard financially, and in his endless search for better opportunities he moved Clarice and her sisters to Rio de Janeiro, then the capital of Brazil, where in 1937 Clarice gained a place at the prestigious National Faculty of Law. Her first success as a writer came soon afterwards when her first known short story "Triunfo" appeared in the magazine Pan in May 1940. Hot on the heels of this success came personal tragedy when her father Pedro, to whom Clarice was extremely close, died at the age of 55 after an operation went wrong.

Having decided that she was too sensitive for life as a lawyer—the tiniest things moved her

to tears—Clarice started working as a journalist whilst still at law school, writing for

the prominent newspaper A Noite. By the time she graduated she had met her future husband,

Brazilian diplomat Maury Gurgel Valente. They married in 1943 and Clarice embarked upon the

itinerant life of a diplomat's wife, living in Italy, Switzerland, Britain and the USA, and

bearing him two sons before depression and homesickness drove her to leave him and to return to

Rio de Janeiro in 1959. She remained there for the rest of her life, and died of cancer in

1977 on the eve of her 57th birthday, shortly after the publication of The Hour of the Star.

Having decided that she was too sensitive for life as a lawyer—the tiniest things moved her

to tears—Clarice started working as a journalist whilst still at law school, writing for

the prominent newspaper A Noite. By the time she graduated she had met her future husband,

Brazilian diplomat Maury Gurgel Valente. They married in 1943 and Clarice embarked upon the

itinerant life of a diplomat's wife, living in Italy, Switzerland, Britain and the USA, and

bearing him two sons before depression and homesickness drove her to leave him and to return to

Rio de Janeiro in 1959. She remained there for the rest of her life, and died of cancer in

1977 on the eve of her 57th birthday, shortly after the publication of The Hour of the Star.

Clarice Lispector shot to literary fame in Brazil with the publication in 1944 of her first work, Near to the Wild Heart (Perto do coraçao selvagem), hailed by critics as a watershed in Brazilian literature. Breaking with Brazilian literary tradition, Lispector's work is clearly influenced by European literary movements, in particular existentialism and the nouveau roman; there are also echoes of Woolf, Chekhov, Joyce, and Katherine Mansfield. She wrote over twenty volumes of fiction, non-fiction and children's fiction, several of which have been translated into English.

I had been keen to read Lispector for some time, so when Belletrista's Editor asked if I was interested in writing a Trio feature on her for this special Latin American issue, I jumped at the chance. The books I chose are Near to the Wild Heart (Perto do coraçao selvagem), Family Ties (Laços de Famália) and The Hour of the Star (A Hora da Estrela). The first and third are short novels or novellas, and as they are the first and last books she published during her lifetime, they provide an overview of her whole career. Family Ties is a collection of short stories which I included for a glimpse into Lispector's handling of another form (and because I like short stories). All three are translated by Giovanni Pontiero; whilst I'm a great admirer of Pontiero's work, if I chose my Trio again I'd include something by another translator (Alexis Levitan's translation of Soulstorm, for example, or Gregory Rabassa's rendition of The Apple in the Dark) just to see if Lispector's very individual voice comes across differently in other hands.

Near to the Wild Heart

Near to the Wild Heart

(Perto do coraçao selvagemi)

Translated from the Portuguese by Giovanni Pontiero

New Directions, paperback, 9780811211406

Lispector wrote her first novel in a fevered 10-month burst of activity in 1942, and her efforts were rewarded with critical acclaim and the presitigous Graça Aranha national prize for fiction in 1944. To read it is a disconcerting experience. The non-linear narrative perfectly reflects the protagonist's turbulent inner life as it takes the reader on a dizzying yet exhilarating series of shifts and jumps, constantly returning to things from slightly different perspectives. We meet Joana as an unconventional child, already more interested in thinking than in playing. Sent to "make up another game" by her father, instead she muses,

As an adult Joana continues to grapple with philosophical problems and struggle with issues of identity—she is the precursor not only of many of Lispector's later protagonists, but of so many female characters in twentieth and twenty-first century literature. The adult Joana conforms outwardly, her marriage to Otávio casting her in the role of conventional suburban housewife, yet her inner monologue reveals her search for an authentic existence:

Continuing to muse on the same theme—can a woman adjust to marriage and retain her identity?—Joana eventually concludes that in marrying she has betrayed herself, and she becomes determined to seek freedom, whatever the cost. Her coldness drives her husband back to the arms of his former fiancée, and Joana herself becomes involved with a mysterious "Man" whose name she prefers not to know—"the mystery clarifies more than any revelation". In her anguished search for the authentic, Joana loses interest as soon as anything ceases to be mysterious; her encounter with "the Man" at last provides her with a feeling of freedom, taking her away from "that zone…where everything has a solid and immutable name".

The quote from James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man which serves as the novel's title was suggested to Lispector by an older writer friend, and no doubt spurred critics on in their rush to identify Joycean touches in Near to the Wild Heart—although the ever-enigmatic Lispector always claimed not to have read Joyce when she wrote it.

Family Ties (Laços de Famílía)

Family Ties (Laços de Famílía)

Translated from the Portuguese

by Giovanni Pontiero

Univ. of Texas, paperback, 9780292724488

Carcanet Press LTD, paperback, 9780856359897

The thirteen stories in this collection are all born out of nothing; in each, a trivial instant—the kind of instant the mainly female protagonists' lives have been full of so far without event—takes on huge importance and changes everything as the character acquires self-awareness, and through it freedom and anguish. Action is thin on the ground; this is inner-monologue territory, stream-of-consciousness narrative used to stunning effect.

Nor are the characters particularly important, at least not as individuals; rather, it is their circumstances that Lispector is interested in, their moments of crisis and how they react. The individual characters are drawn in strokes broad enough for them to be general representatives of Everyman and Everywoman—for couldn't every one of us be hit by a crisis as we eat dinner in a restaurant (like the protagonist of "The Dinner"), as we sit on the tram ("Love"), or even as we read the colour supplement ("The Smallest Woman in the World")? The universality of the characters makes them poignantly human, and therefore strangely memorable despite their lack of specific traits.

The "family ties" of the title are both ties that link and ties that bind, and many of the stories feature a character chafing against family bonds. One of my favourites from this point of view is "Happy Birthday", set at a birthday party for an old woman who has suddenly realised that she has no patience left for her family. Other themes that cut across many of the stories include awareness of the passage of time and of the inevitability of death, wonderfully summed up in the last line of "The Chicken", a very short story about a chicken attempting to escape the cooking pot:

Almost fifteen years after Near to the Wild Heart, Lispector still revels in causing her reader discomfort; these aren't stories to curl up in front of the fire with. The inner monologues here are less dizzying than in Near to the Wild Heart, as they are limited by the length of the separate stories (most of them are under ten pages), but they are no less disconcerting. The reader shares the characters' anguish as they realise that they are free, their sense of nausea at the realisation that they are often not up to the challenge of freedom, and their bewilderment as they become aware of the absurdity of life.

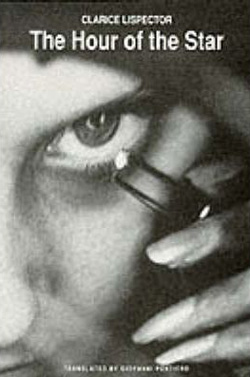

The Hour of the Star

The Hour of the Star

(A Hora da Estrela)

Translated from the Portuguese by Giovanni Pontiero

New Directions, paperback, 9780811211901

Much as I enjoyed the first two of my Trio, The Hour of the Star is my hands-down favourite. It's a tiny little novella (well under 100 pages) that packs an enormous punch. Just like the other two it's hardly a relaxing read, though it's hugely rewarding. I'm pleased I didn't come to it cold, as I think that what I learnt about Lispector on the way helped me appreciate this book more.

Although Lispector didn't know she was dying (her cancer diagnosis was kept from her), in the last months of her life she was filled with nostalgia for her early years in the poor northeast of Brazil. This novella, published just before her death, is the haunting story of Macabéa, a desperately poor girl from the northeast who has come to the Rio slums to try to make a living as a typist. Lispector dedicates the novella to, amongst many other people and things, "the memory of my years of hardship when everything was more austere and honourable, and I had never eaten lobster".

Lispector doesn't present Macabéa to us directly; instead she interposes a male narrator, the urbane Rodrigo S.M., who has caught sight of Macabéa on the street and is fascinated by her and what he supposes to be her entirely miserable existence. Rodrigo's narrative adds a delicious twist. How much of what he tells us can we believe? Isn't his whole view of Macabéa based on no more than a glimpse of her? How much of what he says is him and how much is Lispector herself? Does it matter? Rodrigo's keenness to tell the story prevents him from doing so; he spends the first third of the book explaining why it is so very necessary that the story be told, and that he tell it, and even when the telling starts we can't help but wonder about little inconsistencies in his account—and we certainly can't forget his presence, as his narrative is sprinkled with phrases like "as I've said" and "it seems to me".

It's true that Macabéa lives a miserable life. Her job is a dead-end and on top of that she can't even do it properly; her boyfriend is a rat and she can't keep him; she's not just poor and sick but ugly too. Her only awareness of life beyond the confines of her own existence comes from random facts churned out by the radio station she listens to— and yet (and this is what infuriates Rodrigo and challenges both his and the reader's notion of poverty) she doesn't seem to realise that she shouldn't be happy. As her story goes on she achieves real moments of happiness, albeit ones which would provide happiness only to someone as wretched as she is.

Many of the themes from Family Ties resurface in The Hour of the Star: the identity and role of women, for example, and the inexorable passing of time leading to certain death. The end of The Hour of the Star harks back to the closing sentence of "The Chicken" quoted above:

When I return to the quote from Cixous with which I began, three books into my Lispector reading

experience I can see what she means. Lispector confounds my expectations, makes me so

uncomfortable that I want to stop reading, makes me so uncomfortable that I can't stop reading,

makes me squirm, makes me cry…and then she makes me laugh, which has been the biggest surprise

of all.

Rachel Hayes is a Brit living in Belgium. She reads a variety of mainly contemporary fiction, and

enjoys seeking out translated fiction from areas of the world her literary travels haven't

taken her to before. She attributes her interest in books written by women to an early obsession

with Little Women, What Katy Did and The Chalet School.