International PEN "Free the Word!" Festival, London. April 2010

As I write this, Britain is in the grip of election fever: in early May we go to the polls to select our new

government. This is a time of middle-class, middle-aged white men stringing out platitudes and watered down

policies that no longer have any ideological standing or heart.

As I write this, Britain is in the grip of election fever: in early May we go to the polls to select our new

government. This is a time of middle-class, middle-aged white men stringing out platitudes and watered down

policies that no longer have any ideological standing or heart.

On 15 April the Egyptian author, feminist and political activist Nawal el Saadawi was interviewed by author Lisa Appignanesi before a small but appreciative audience at the Southbank Centre in London. Forthright, polemical, honest, she was a breath of fresh air in an atmosphere of tired political debate.

Born in 1931, el Saadawi grew up in a small Egyptian village as one of nine children. Although she remembers her brother having preferential treatment on educational opportunities because he is male, she also received an education and went on to Cairo University to study medicine, graduating in 1955.

So with a medical career in front of her, what prompted her to begin writing? To her writing was completely

natural, 'like breathing'. El Saadawi remembers being told as a child that she couldn't write, but she knew

that 'the minute you speak, your mind writes'. She believes that the way children are taught, in all countries,

diminishes this innate creativity.

So with a medical career in front of her, what prompted her to begin writing? To her writing was completely

natural, 'like breathing'. El Saadawi remembers being told as a child that she couldn't write, but she knew

that 'the minute you speak, your mind writes'. She believes that the way children are taught, in all countries,

diminishes this innate creativity.

While one might think that the practical profession of medicine and the creative activity of writing might be hard to balance, el Saadawi is adamant that her experiences as a doctor are essential to her art, saying that being brought face to face to death, to know about death, is important for all artists. That her first novel, published in 1958, was entitled Memoirs of a Woman Doctor shows how closely her work and her art are connected.

It's easy to see how el Saadawi's childhood and her early medical career, working in her home village, shaped her writing and her politics. From a very young age she had an awareness of the oppression of women, an awareness that continued grow to as she saw the effects of patriarchy and poverty on the local women she worked with. She states that she gained great insight from working with sick people, both there and later in Cairo, that informed her future—in Egypt 'the more you know, the more you rebel.'

Working as a doctor has led el Saadawi to protest vociferously against female genital mutilation (FGM) and male circumcision for several decades. She speaks of her astonishment at discovering the extent to which the Sudanese women who she attended in hospital had been cut, a religious and cultural mutilation that she condemns as 'ridiculous'. She started to get angry about genital mutilation and wrote against it in books and articles, notably Women and Sex which was published in Cairo in 1969. This outspokenness drew the attention of religious authorities and the Egyptian government. A taboo subject then (and now), el Saadawi's condemnation of FGM was declared to be against God. Her unflinching stance on this subject contributed to her losing her job as Director General of Public Health in 1972 and led to the government's closure of Health, the magazine she had founded and edited for several years.

Female genital mutilation was finally outlawed in Egypt in 2008. However, el Saadawi continues to campaign against male circumcision—she is against the cutting of all children, male or female. She explains that she is battling against the medical profession as well as religious bodies of all minds. She told us that even in Europe doctors are unconsciously affected by religious sensibilities, that this thinking is 'deep-rooted' in the psyche, reminding the audience that this mutilation of children is related to a universal patriarchy.

El Saadawi is perhaps at her most strident when condemning this universal patriarchy, the religious fundamentalism that supports it across the world, and the resulting oppression of women. The murmurs of agreement and applause from the audience suggest that her views are shared by many of the women there. She reminds us of the role that colonialism has played in developing this oppression and argues that George W. Bush is partly responsible for female genital mutilation, explaining that the British and Americans have encouraged religious fundamentalism to further their own colonial ambitions. This was argued with good humour, a trait that was ever-present during the event.

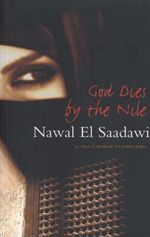

Through the 1970s and 1980s el Saadawi continued to write and campaign, publishing novels, short story collections, non-fiction works and many articles. Much of this work focused on the oppression of women. Her 1984 novel God Dies by the Nile, for example, is about a young illiterate woman's growing political awakening as she comes to understand that all of the awful things that happen to her and around her are the result of hierarchy and patriarchy. They are not God's will as she has been led to believe, a realisation that has fatal consequences.

In September 1981 the opposition to el Saadawi's activities came to a head and she was imprisoned for

two months. While incarcerated she wrote her book Memoirs from the Women's Prison on a roll of

toilet paper with an eyebrow pencil that was smuggled into her cell by a young woman from the prostitutes' ward.

In September 1981 the opposition to el Saadawi's activities came to a head and she was imprisoned for

two months. While incarcerated she wrote her book Memoirs from the Women's Prison on a roll of

toilet paper with an eyebrow pencil that was smuggled into her cell by a young woman from the prostitutes' ward.

With the publication of further works and articles that continued her condemnation of patriarchy and injustice, el Saadawi's name started to appear on death lists issued by religious fundamentalist organisations in Egypt. In 1991 the government closed down the local branch of the Arab Women's Solidarity Association and its magazine Noon. El Saadawi explains that this was because the Association was publicising the connections between women's oppression and the political, economic and cultural life of Egypt. That same year el Saadawi's life was threatened by religious fundamentalists and she moved to the USA where she lived for a number of years.

Now living back in Cairo, el Saadawi's writing and activism continues to provoke the Egyptian authorities. In 2001 three of her books were banned at the Cairo International Book Fair. In 2002 a fundamentalist lawyer brought a case to have her forcibly divorced from her husband because she is 'anti-Muslim'.

Listening to her speak, you start to get the impression that el Saadawi enjoys the controversy! She once stood for election as President of Egypt, a move that she explains was a symbolic gesture, a 'test of democracy' to show women that they have a place in politics. Her responses to questions from Lisa Appignanesi and the audience sometimes seemed deliberately provocative. At one point she claimed that it's impossible for women and men to have equality in marriage, citing her two divorces as evidence of this! I have to report that none of the men, or the women, in the audience got up to challenge her on this.

It was perhaps inevitable that once the floor was opened to questions, there would be mention of the British

election. A woman asked for el Saadawi's opinions on women wearing the veil. The far-right British National

Party wants to ban women from wearing the veil. However, this seems to be causing many young women to take

the veil in protest against this. El Saadawi reminds us that the veil is a political symbol being used

by the BNP in a political game. She can't defend the veil just because the far-right parties say they are

against it. She explains that for her the veiling of women in Islamic societies and the nakedness of

women in 'Western' societies are two sides of the same coin; both are a sign of the continuing oppression

of women. And as for Barack Obama's claim while speaking Cairo that Egyptian women are free to choose to

wear the veil? 'Rubbish!'

It was perhaps inevitable that once the floor was opened to questions, there would be mention of the British

election. A woman asked for el Saadawi's opinions on women wearing the veil. The far-right British National

Party wants to ban women from wearing the veil. However, this seems to be causing many young women to take

the veil in protest against this. El Saadawi reminds us that the veil is a political symbol being used

by the BNP in a political game. She can't defend the veil just because the far-right parties say they are

against it. She explains that for her the veiling of women in Islamic societies and the nakedness of

women in 'Western' societies are two sides of the same coin; both are a sign of the continuing oppression

of women. And as for Barack Obama's claim while speaking Cairo that Egyptian women are free to choose to

wear the veil? 'Rubbish!'

Whether you agree with all of her views, there is no denying that Nawal el Saadawi is a woman of great conviction and courage. Her ongoing activism against oppression and her many political and artistic achievements, of which only some were touched on during this event, are inspirational.

Charlotte Simpson lives in London. She reads a wide range of classic and contemporary fiction written

by women. She has a Masters degree in Modern British Women's History.

Zed Books, paperback, 9781848133358

Zed Books, paperback, 9781842778739

Zed Books, paperback, 9781842778777

Univ. of California Press, paperback 9780520088887

Zed Books, paperback, 9781848132269

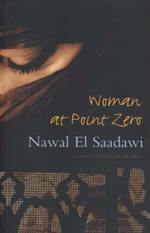

Interlink, paperback, 9781566567329

This is just a small representation of Nawal el Saadawi's books, for more information please visit her website.