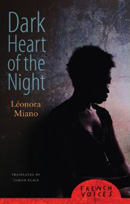

Few English translations can have had such an awkward birth as that of Léonora Miano's slim novel, written in 2005 in French as L'intérieur de la Nuit. The University of Nebraska Press made the laudable decision to publish an English translation of this work by one of the most promising young francophone African writers around; however, a crass interpretation of the title and a foreword that completely misses the novel's point prompted a venomous six-point rebuttal from Miano (unsurprisingly it isn't included in the book, but is available online), and re-ignited a debate about the representation of African literature by Western publishers.

Having read Dark Heart of the Night, it's easy to sympathise with Miano's frustration. The story is about a single night in the lives of villagers in a small rural community in a fictional African country. The village is occupied by young soldiers in a revolutionary army who are determined to instil their version of pan-African identity into the villagers. The villagers are forced to commit an horrific act of cannibalism, something that the soldiers see as a ritual harking back to pre-colonial Africa. This event is witnessed by Ayané, a villager who had left for Europe years before, but has returned to be with her dying mother.

The situation allows Miano to juxtapose several versions of African identity. The villagers are ethnic 'Eku', who have no large concept of Africa, and who do not look beyond the bounds of their own village. Ayané's mother Aama is an outsider, shunned because she comes from a different Eku village. Ayané is rejected because of her mother's identity and her emigration to the city, then to Europe, and because she is quick to reject what she sees as the excesses of her home continent as a whole. The soldiers gain their African identity from the mythology connecting the Eku to other tribes, but it is a reactionary identity warped by colonialism and the definitions of Africanism forced on them by Europeans. Miano skilfully uses the cannibalistic ritual to explore the consequences and assumptions behind these differing interactions between individuals and their definitions of what it means to belong to Africa.

The book is a harrowing account of a single, bloody event, translated by Tamsin Black (with the

exception of the title) with care and precision. Although the characters are somewhat allegorical, Miano

creates believable flesh-and-blood individuals in a very small number of pages, resulting in an involving,

gripping and thought-provoking book. At less than 150 pages, the prose is necessarily sparse, written like

a good short story. Reading Dark Heart of the Night requires both a strong stomach and an open mind,

but it is a book worth seeking out. The simplicity of both prose and narrative provide relatively easy

access to what is a complex and involved debate, and Miano's novel is a fantastic achievement.

All of which makes Terese Svoboda's foreword mystifying. Miano's subsequent criticisms are aimed firmly at an American publishing industry that seems determined to foist its own interpretations of what 'Africa' means onto its book-buying public. The translation of the title as The Dark Heart of the Night is needlessly reminiscent of Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad's questionable take on African identity that has stood for a hundred years as a monument to white Western attitudes towards the continent. But it is Svoboda's foreword that really incenses Miano. Svoboda mislabels the book as a critique of pan-Africanism, erroneously criticises Cameroon's human rights record, shortens Miano’s publication history, and misrepresents events within the book. Miano intended her novel to be about 'Africa' in the conceptual sense, so Svoboda was correct to phrase her introduction in those terms. Her error, was to make groundless assumptions about what 'Africa' means to Miano. Miano's reply is perhaps needlessly waspish, questioning both Svoboda's ability to read and American tastes in general, but then it must be frustrating for a writer when a misleading foreword is attached to her work, one that will inevitably misdirect a good proportion of its English language readership. All I can suggest is that you get hold of the book, ignore the foreword and read the narrative carefully. Controversies aside, The Dark Heart of the Night is a powerful and thought-provoking read, and an unsettling short novel by a very talented writer.

Bison Books, paperback, 9780803228238