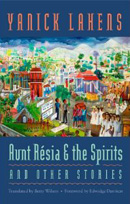

It's always good to be reminded of the diversity of talent from places that the rest of the world focuses on only in the most troubled times. Even before this year's terrible earthquake, Haiti was a by-word for poverty and violence. This anthology of short stories by Yanick Lahens, a first English translation for one of Haiti's foremost short story writers, is a timely reminder that the country has so much more to offer the world.

Aunt Résia and the Spirits includes short stories taken from three previously untranslated collections published in French between 1994 and 2004. Most of the stories are very short, ten pages or less. They are all (with one exception) set in Haiti, often amongst the shanty towns and rural communities that make up the majority of Haiti's poverty-stricken population. Lahens examines the fragility of existence in her home country. Lives are casually snuffed out, and the line between petty crime and murder is a thin one. Many of the stories are beautifully written, emphasising the tragedies inherent in the lives of the characters, whether they be innocent victims of crime or the young men committing them. Lahens' stories leave much unsaid. In "The Green Room", a mysterious presence in her home disrupts a young girl's life, and it is never explained to her who the strange man she glimpses is. Likewise, in "The Survivors", a young man dies a violent death without explanation. In later stories, such as "An American Story" and "Three Natural Deaths", Lahens concentrates on the nexus of events that sustains the violence. The longer story "The City" showcases a different Lahens, writing both fondly and mournfully about a man returning to a city (presumably Port-au-Prince) that he has left long ago, and observing the new reality of his home.

Yanick Lahens is a very good writer, and Betty Wilson's translation is seamless. Lahens' stories are

perfect examples of short narratives: sparse, powerful and complete. There is a relentlessness and

humourlessness that makes this a fairly emotionally draining read, but then she is writing about emotionally

draining subjects. A well written afterword places Lahens firmly within the greats of Haitian literature,

and also gives a glimpse into the depths of Haitian talent that remain untranslated and largely unknown.

This is a great collection of short stories, and a first opportunity for English speakers to discover one

of the finest exponents of the art in the French speaking world.

CARAF Books (Univ. of Virginia Press), paperback, 9780813929019