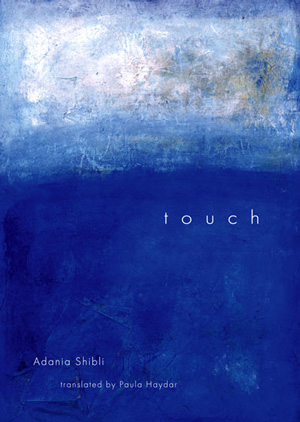

Having debuted in our previous issue, "Conversations" is featured again in this issue with a different group of readers and a very different book. This time, we are discussing Touch by Palestinian author Adania Shibli, who was once touted as the "most talked about writer in the West Bank". She has twice been awarded the Young Writer's Award in Palestine by the A. M. Qattan Foundation. More recently, Shibli was chosen as one of the thirty-nine winning young Arab writers, under the age of forty, to participate in the Hay Festival's "Beirut 39" program. She has written plays, short fiction, and essays, and is the author of two novels, Touch and We Are All Equally Far From Love, both published in Arabic by Al-Adab, in Beirut. Beautifully translated by Paula Haydar, Touch was published in English this year by Clockroot Books. It is a small book—a mere 72 pages—divided into five sections: "Colors", "Silence", "Movement", "Language" and "The Wall". The book features an observant lonely little girl, the youngest in a family of nine sisters in a Palestinian family. She spends a lot of time alone, perceiving the world around her, and being amazed by it. She takes pleasure in the little things, like solitude, and the sights and sounds around her. Although the novella is set in Palestine, the events in the country remain on the periphery. One is only aware of it to the extent that the young protagonist is aware it. This is a beautiful, thought-provoking piece of work that subtly considers the connections between a child and her family, and the family and its connection to the broader community.

Participating:

Barbara, 46, A marketing processor from Ohio, USA

Amanda, 50, A music teacher from Sydney, Australia

Dan, 37, A geologist from Texas, USA

Dan: I looked forward to reading Touch because I knew the author is a Palestinian woman and I had heard it was reflective which, sounded like very a interesting combination. Certainly my own Jewishness played a roll in my interest. I didn't expect it to be so poetic and beautiful. It's a slim book, a collection of short sketches that leave evocative impressions, which aren't always so clear, but leave something to think about. I enjoyed reading it, and rereading it.

Barbara: My experience with the book was somewhat similar to Dan's. Upon first reading it, I was often confused by subtle

cultural references, which may have been crystal clear to an Arab reader. The novel's lack of action and shifts in time were

also sometimes difficult to follow. At points, I felt like I was reading a cross between a Henry James novel and the film

"Memento". By the end of the book, the narrative fell into place. I then re-read the book and picked up on many more details

than I had the first time around.

That being said, I very much enjoyed the book, especially Shibli's poetic style.

Her descriptions of events in terms of colors were particularly evocative and beautiful.

Amanda: This was a first for me—the first Palestinian author I had ever read, so I was very interested to discover

Touch. I was also interested that the author chose not to dwell on the fighting in the Gaza Strip but referred to it only

through the death of the girl's brother and the incidents at Sabra and Shatila (which I had to look up on Wikipedia). So, rather

than a story of bombing and soldiers and blood, we have the story of one girl.

Coming from a Palestinian author,

were you expecting the content of the book to be more like a war story? Did you like the way she dealt with the brother's death?

Dan: Amanda, I read some reviews before I started the book, so I knew it was a reflective work and was not expecting a war story.

I did not know the time period, and certainly was not expecting Sabra and Shatila to have a prominent place in the effect of

this book, which is set in the West Bank in Palestine, not Lebanon, where the massacre took place. When I read through this the first time I

realized there was a lot of subtle information that I was missing, and probably a whole lot of symbolism that I will

never get. (If anyone has insight here, please pass it on). So instead, I focused on just taking in the images and the overall

structure. I found it compelling, but also confusing in that so little is revealed up front. Slowly and subtly the book begins

to reveal itself and it sort of backfills itself in with texture. It's an interesting effect. Sabra and Shatila, names I've heard before,

seemed to arrive out of context. I couldn't place them at first, and continued to read, puzzling over them, and then it clicked.

And just like that, near the end of a 72-page book, it hit me in the gut.

Sabra and Shatila deserve a proper

introduction: the massacres took place in 1982 in an Israeli-controlled part of Lebanon. The victims were Palestinian

civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. What makes it an especially dark episode is that the whole thing was

orchestrated by the Israeli military. I don't understand the details around it, and my own Judiasm gives me an unnaturally conflicted

viewpoint that I've found difficult to resolve.

If the book worked for you, at what point did you connect with it?

Was it up front, or a delayed response?

Amanda: Dan, I connected with it immediately because of the writing style. To me this novella is like a tiny jewel. At a mere 72 pages and with the deceptively plain writing, one could almost overlook its merit. But there is so much poetry in the writing and I would have been happy to read it for that reason alone. My second reading made the poetry and the mood all the more powerful to me. Did you like the style? Or the way the book is divided into "Colors", "Silence", "Movement", etc.?

Barbara: I like Amanda's idea of talking about how the book is divided. I am also interested in hearing what you both thought about the

central character's perspective. I thought the author did a remarkable job of capturing a child's perspective by focusing

on things that children notice and omitting things that children don't notice or understand. For example, there is a lovely

description of how rust from a water tank made a delicate, sparkly glove on the girl's hand. Much of what happens in the story

is told through the girl's direct senses, and her lack of understanding is communicated through her senses also. A great

example of this is how the girl learned about the massacres at Sabra and Shatila. She heard the words on the television set,

but could make no meaning out of them.

It is interesting to me that neither of you were very familiar with Sabra

and Shatila. I had never heard about these massacres until I married a Palestinian. I think it is unfortunate that it is not

more familiar to those outside Arab communities, because it is such an emotional touchstone for Palestinians.

Amanda: Barbara, I completely agree with your comments about Shibli's successful creation of a credible child character. What a quirky girl she was, and what a sad inner life she had. Somehow her own behaviour caused her to be rejected by others and then she reacted by isolating herself further, for example, sitting alone in the car. One of the chapters of the book was called "Silence" and for me that almost summarised the little girl's world. Loneliness and silence.

Dan: Amanda, yes, I do like this style quite a bit, although I think I have maybe a

strange response to it, here and elsewhere. The writing is poetic, and I think the reader is supposed to simply enjoy

the poetry. But I don't do that, instead I approach it as something of a mystery to be solved. Where I

am in the book, not understanding what is being said, yet able to see and feel the compassion behind it, was

fascinating and it got me wondering. Answers tend to remain elusive. I've now read through Touch three times

and there are still many obscurities.

Other places I've come across a similar style include Herta Müller's first book Nadirs (or Niederungen), and

Sandra Cisneros' Woman Hollering Creek. There are actually a lot of parallels to Nadirs. The perspectives

are similar; a young girl's perspective of a difficult environment, but described through the grown woman's voice.

Nadirs, however, is far more bleak and

hopeless. The girl in Touch is loved even if she doesn't feel it or always benefit from it.

Barbara: I was struck by Dan's comment about "touch" as well. Until he pointed it out, I hadn't consciously noted the importance of touch in the story, but now it seems so obviously important. The girl seems to be physically affectionate and playful with her father. She is clearly physically affectionate with her neighbor. The only touch from her mother and siblings, however, seems to involve slaps and bruises.

Dan: I haven't quite figured out the main character yet. I don't know her age, and I can't tell whether or where her age changes. Silly as it sounds, I took some notes and discovered that there seems to be a chronology within each section. But, the sections themselves repeat the chronology. In each section we have different view of the boy's death, and therefore a before and after. Also, each ends with the girl in a wedding dress or married, so, at least in that last chapter she is older. This is my long way of saying I'd like to look at the main character more. What were some of the observations you picked up about the girl?

Barbara: Can we infer much about her personality? I didn't feel that I could. It also didn't seem necessary to do so. By stripping down her perspective to only her outer senses, it becomes a more universal perspective. I identified with the girl's confusion and desire to be acknowledged and understood. It enabled me to recall some of my own childhood experiences, even though on the surface, my childhood was very different from the girl's. Is she likeable? I don't know that she's likeable or unlikeable. I don't know enough about her. At times I empathisized with her and at other times I was frustrated by her inability to connect with her mother and siblings.

Amanda: Barbara, I just accepted her as she was and had great sympathy for her because she was only a child.

Dan: Hmmm, what we infer about the girl? She is so young, as to be both innocent and a blank slate. She is also

remarkably passive. She observes everything, and actively separates herself from those around her. When she encounters

her mother in the kitchen in the middle of the night, and expects anger: "Before the mother's mouth opened, the girl

mustered up all her indifference." She often escapes into silence, and enjoys it. When her hearing returns, from a

temporarily deafness, "the paradise of silence disappeared". She enjoys hiding in the car, looking out through the

rear-view mirror.

She doesn't reveal herself, but hides herself fiercely, presumably as a form of escape. But also as a response to the

helplessness she feels, which is so wonderfully expressed in the smoke from her fathers cigarette: "She chased the

cigarette in her father's hand, trying to cut off the rising smoke with her fingers before it spread out in all

directions. She tried hard to cut it off, but she could not stop the smoke, which curled around her fingers and

continued to rise and disperse."

"

Amanda: Was she being sexually abused by the neighbour?

Barbara: Good question. I didn't think that she was being sexually abused by her neighbor, but I'm not certain. I assumed they were around the same age. I actually thought that it was the neighbor she ended up marrying. Did I have that wrong?

Amanda: I'm almost certain that on one occasion she refers to him as the "old" neighbour. And they play evol and it's a secret.

Dan: Wow, Amanda, was that abuse? I'll have to check that again, but my impression was that her neighbor was of a

similar age and that their game, evol, was an exploratory game of two children in desperate need to feel love. The game is

the link to the title "Touch".

Barbara, I was also really struck by how sensory everything is, how careful the

visuals are described, the colors, the car rear-view mirror, and always the light. And sounds, a whole section on silence,

and loneliness. Touch, however, as a sensation, is not everywhere. It doesn't naturally fit into any section and, as it's

the title, I would argue it's distinctly missing, except in this one game. Surely that was important to Shibli; but, how?

Barbara: I'm wondering if the narrative is supposed to remain somewhat mysterious to the reader. A few reasons for

this come to mind. Adult events are often mysterious to children, therefore the author is holding true to the child's

perspective. It may also be a metaphor for how disorienting and without clear cause and effect daily life is in the West Bank.

I had a conversation yesterday with a friend who had lived for several years in Asia. She observed that Americans were more

interested in the facts of an event than many other cultures, and less comfortable with fluidity or metaphor. Perhaps this

is why you (Dan) and I were uncomfortable the first time we read it! At any rate, many Latin American writers come to mind

when I think of this fluid style of presenting events, including Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and as you mentioned, Sandra Cisneros.

Amanda:Barbara, you mentioned yours and Dan's initial discomfort with the book, which I did not feel. Living in Australia, I am geographically and culturally removed from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Australia has a very small Jewish population and I have never met a Palestinian. The Sabra and Shatila incidents would have been to me just two more acts of violence in a never-ending conflict. AN ASIDE: I have read enough to form an opinion on the conflict. I always think of Northern Ireland where I never expected to see peace, but it did come. I hope the same will happen one day in the Middle East.

Barbara: Amanda, my discomfort with the book had nothing to do with the topic. I grew up in the New York area with a Jewish best friend. I was pretty strongly pro-Israel until adulthood. In college, I was very aware of the bombing in Lebanon (as Dan mentioned) and was mildly anti-Arab because of it. All of this changed when I met my Palestinian husband. It bothers me greatly that Americans don't necessarily receive the same news as citizens of other countries. How can we evaluate our foreign policy properly if we don't have all the information? For this reason, I very much welcome an open dialogue on the Israeli-Palestinian issue.

Dan: Amanda, it's very confusing to me, my reaction to Israel/Palestine. Sabra and Shatila were not things I heard

about as a child, yet they happened in 1982 when I was nine years old and attending Hebrew school on Sundays and supposedly

learning all about Israel. Obviously this was censored, and maybe that's OK for a nine-year-old, but it didn't come up

later either. I can't really express how strange that is to me. I did not have a censored childhood. I mean the 241 American

soldiers who died in Lebanon in 1983, that was front page news and we still hear about it all the time. And yet I can't

recall ever hearing about Sabra and Shatila from a major news organization, even during Sharon's election in 2001. (You can

find a few articles with a google search.)

Ok, so I probably should get back on topic with the actual book. I think part of the art is keeping the child's perspective

and also maintaining that poetic voice. So, we get a third person story that feels autobiographical, that is confusing and

wondrous at the same time...but wondrous of a complex and somehow bleak world. But things are revealed, just not in the way

we might expect them to be. So, my question, what does all this say about the West Bank? And is it only valid for 1982,

or does it carry over to today?

Barbara: Dan, I have never visited there, and even my ex-in-laws left in the 1960s so what I'm about to say is purely conjecture on my part. The description Amanda had of the girl struck me as possibly being a metaphor for those in the West Bank: "Somehow her behavior caused her to be rejected by others, and then she responded by isolating herself further." I also wonder if the girl's pain over having to choose between the betrayals of her two parents is a metaphor.

Near the very end of the book, the eighth sister justifies the mother's and sisters' silence as follows: "Their silence did not mean the absence of love, but the father's unfaithfulness was the absence of love." The girl rejects this statement, and makes no more attempts to reach out to the sisters. I wonder if this represents a feeling of betrayal on the part of the Palestinians for those who claim to support them. Perhaps this includes other Arab countries as well as the U.S.? Also, the final chapter, The Wall, may be a metaphor for the wall built by Israel in the West Bank. ("It encompasses all vision...she can't escape it.")

Amanda: Yes, that was the only "wall" I could think of but I didn't understand how it might relate to the content of the final chapter.

Barbara: I thought of it as an insurmountable wall between herself and her mother and siblings. The last image is of her looking in the rearvew mirror at her house disappearing. I got the sense she would no longer try to build a rapport with her family, that she was closing that chapter in her life.

Dan: You both have me thinking of the book in a new light. Suddenly, everything is a metaphor for the current Palestinian situation. The wall (I missed that), the partially voluntary isolation, the difficult love/hate relationships and confrontations with the sisters and brother.

Amanda: Barbara and Dan, Thanks for explaining the final chapter! I have thoroughly enjoyed this conversation. I've had the opportunity to share what I liked about Touch and I've had some questions answered. It's been fascinating and fun to hear two other perspectives. Also, this conversation made me look at the book again, and much more closely, and that was very rewarding. I've had a wonderful time.

Dan Amanda and Barbara, this has been a wonderful experience discussing this book. It's a potent, complex and layered book that deserves a lot of thought and exploration. I've enjoyed doing this and it's quite fascinating to see our different reactions and learn how our backgrounds play a roll. My advice for anyone thinking of reading this book: Forget everything you're read here. Turn it off and just read the book as blindly as you can. Then, go back and read it again. It won't take long.

Barbara: I knew nothing about this book before it arrived in the mail. I was delighted by its poetic beauty as well. I thought

it was a great choice for a group discussion because there is so much hinted at, but unsaid. To me, the best books are those

that get me to think more deeply, and to create more questions. This book is certainly in that category. I also enjoyed the ambiguity

as to how much, if any, of this book is a metaphor for the Palestinian people. Symbolism may or may not have been the author's

intent, but she certainly provided a forum for future discussions on the topic. For me, it was especially nice to have this

discussion with people with different perspectives from mine.

Touch is well worth reading, and reading again.

Touch by Adania Shibli was translated from the Arabic by Paula Haytar and published by Clockroot Books. It can be found in your local bookshop, your favorite on-line bookshop, or the publisher's website. Clockroot Books will publish the English translation of Shibli's second book, We Are Equally Far from Love, in the Fall of 2011.

If you'd like to participate in one of our future conversations, send us a note at editor [at] belletrista.com.