The interesting point about most of the stories in Karen Joy Fowler's superb new collection is what doesn't matter in them. Most feature some element of the fantastic, which typically would be their point. But here, the fantastic element or idea is always less interesting than Fowler's character or milieu.

Fowler is best known for The Jane Austen Book Club, a delightful, comic novel about six people reading Austen's great novels. But Fowler's range on display here is much wider than the readers of that earlier bestseller might guess, as some examples show.

For me the standout is "Always." An unnamed woman is interviewed about her membership in an absurd religious cult, which has promised her immortality—not in an afterlife, but eternity here on earth—with the demand that she give her life over to the cult's founding charlatan. The frauds and pressures that keep Brother Porter supplied with willing converts are sad and amusing. Fowler's characteristic, dry wit supports her talent for placing her characters vividly in their social environments. But, splendid though her wit is, that doesn't matter, next to her exploration of how her character is changed by a sincere belief that she will outlive mountains and trees. The woman feels absolute conviction on this point, as her sense of time stretches out from the everyday to the geological. This leaves the reader half convinced Brother Porter really has some secret power— but, more, persuaded that that possibility is less interesting than the woman's own story as she tells it. After I read this story it came to mind continually for days afterward.

"The Last Worders" are those attending a particular evening at the Last Word Cafe, somewhere in Europe, where poetry "to the death" is promised. What may have happened at the performance is like no other poetry slam, ever. But what matters is not that glimpse of the fantastic, but the relationship of twin sisters who have come to town in search of a boy they both like, intending to have him choose between them. The viewpoint sister insists too strenously on the closeness and symmetry of the twins' bond, a claim undermined at numerous points. Could a poetry reading change the world for its audience? How does that prospect compare to the old story of control and resistance, played out as the subtext of the sisters' lives?

In "The Pelican Bar," a rebellious teenage girl is sent to a school that is beyond Dickensian in its cruelty. "The Dark" takes us to the underground tunnels of the Vietnam War. "Familiar Birds" again considers the rivalry of two young girls, one of whom claims to talk with birds. In "The Marianas Islands," family entanglements are complicated by a homebrew submarine. "Halfway People" is a sort of fairy tale, with a no-longer-young woman rescuing a castaway who has a wing in place of one arm.

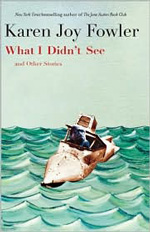

Two stories center on John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, and Booth's family and associates. The Nebula award-winning "What I Didn't See" brings to mind the late writer Alice B. Sheldon, in its title's echo of Sheldon's famous "The Women Men Don't See," one of the finest speculative-fiction stories of the twentieth century. Moreover, its plot, involving a 1920s African safari to bag gorillas for museum display, echoes the similar safaris in Sheldon's life. Here, again, the important point is what its viewpoint character did not see until long after the safari: her and her companions' biases.

Fowler's stories are gripping and surprising, with multiple pleasures

awaiting the reader. Unlike the heroine of "Always," we do not have

unlimited time, but what time we do have is well used by reading—and

rereading—What I Didn't See.

Small Beer Press, hardcover, 9781931520683